By Miles W. Griffis, High Country News

In the hot sun, the sandstone layers of the canyon were like melting Neapolitan ice cream, the strawberry of the Jurassic entrada liquifying under the weight of vanilla and chocolate. I followed a slim trail of pink puddles through archways of junipers and found myself in the landscape depicted in Georgia O’Keeffe’s 1940 painting Untitled (Red and Yellow Cliffs), a trippy oil that shows the precipice that towers over her beloved Ghost Ranch topped by a tiny slice of blue sky served à la mode.

A cloud of bushtits led me to a boulder that had calved off the pastel canyon rim. It was rough as sandpaper and festooned with an eight-inch lizard. She basked in the Southwest rays doing push-ups, displaying her fierce black-and-yellow stripes. When she raised her chin, the powder-blue underside contrasted with the pink hue of the boulder, a color combination that haunted me with visions of viral gender-reveal parties.

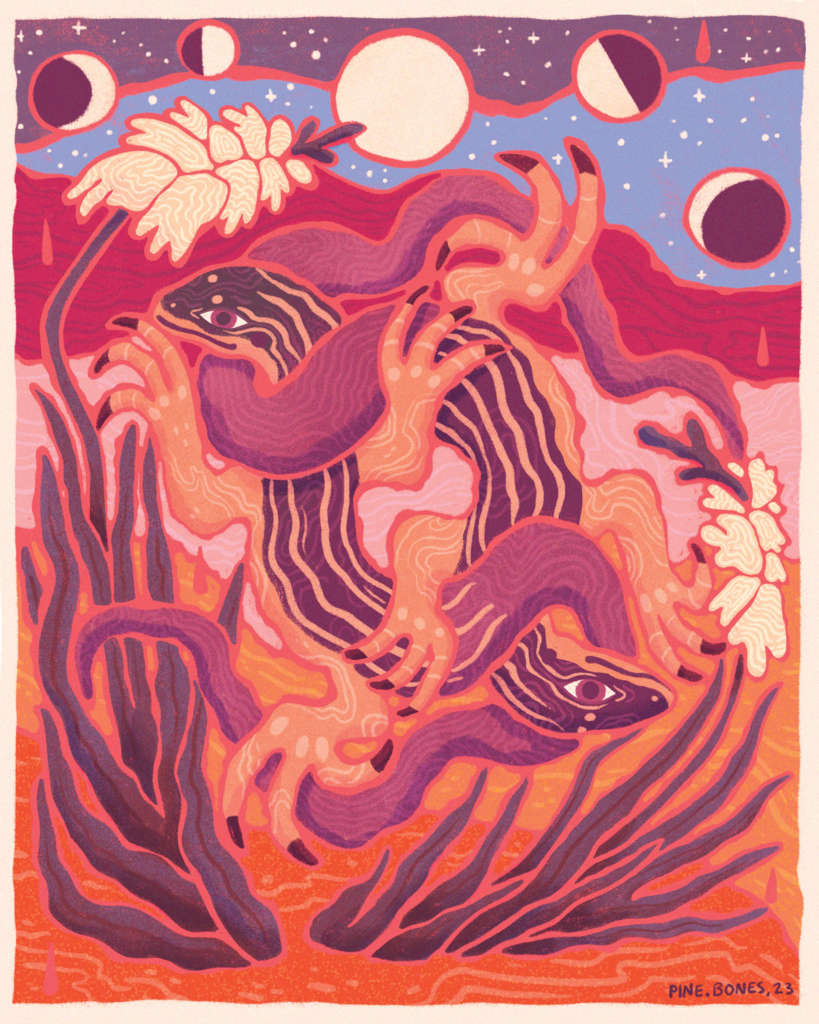

How did I know that she was a she? I had stumbled across the internet’s “gay icon” of herpetology: the New Mexico whiptail. Over the past decade, Cnemidophorus neomexicanus has become an idol for some queer people, because this species’ members are all female. They reproduce asexually through a process called parthenogenesis and yet still display sexual behaviors like mounting. They’ve thus been dubbed the “leaping lesbian lizard” and inspired art, comics, a Pokémon named Salazzle and shelves of online merchandise — even the name of an ultimate frisbee team at Wellesley College. One sticker sold on Etsy portrays two lizards in the seven colors of the Sunset Lesbian Pride Flag, their tails curled in the shape of a love heart.

Over the past decade, Cnemidophorus neomexicanus has become an idol for some queer people, because this species’ members are all female.

Simply put, parthenogenesis is reproduction without fertilization, Hannah Caracalas, a biologist and board member of the Northern Colorado Herpetological Society, explained. She told me that the process is relatively common in plants, as well as invertebrates such as scorpions, but rare in vertebrates. It does occur in some fish, reptiles and birds; in fact, it was recently observed in a pair of female California condors, though these New World vultures primarily reproduce sexually. Parthenogenesis, however, is well known in certain species of whiptails, including the nearby Colorado checkered whiptail (Cnemidophorus tesselatus), whose reproductive behaviors Caracalas has studied.

“There are a series of hormonal triggers that happen around reproduction time that signal to the female to start producing these eggs,” Caracalas said. “She basically copies her own genetic material and passes it off to her offspring.” This means that the mothers and daughters are all clones of each other — they have identical genetics.

While the lizards reproduce fully on their own, the New Mexico whiptail and Colorado checkered whiptail both engage in pseudocopulation, in which one lizard mounts another, bites, and hooks its leg around the bottom lizard’s body, while the two lizards entwine their tails. “It is thought that that kind of behavior will start stimulating those hormonal triggers that will lead to ovulation,” said Caracalas.

When I found a second whiptail on the south face of the Ghost Ranch boulder, I thought of my dry biology classes in high school and college, and how they were framed through a cisgender and heteronormative bias that excluded the full reality of the natural world: Not all species reproduce via male/female pairs. Many species, in fact, including New Mexico whiptails, lack males altogether, and others, like some marine snails, change genders to mate. This same prejudice has been propagated by everyone from historians and academics to Hollywood producers, who have straight-washed queer people and their relationships, from Susan B. Anthony to the artist Mai-Mai Sze and her partner, Irene Sharaff. Whiptail fans joke on online message boards that the cis-het male biologists of yesteryear must have described the New Mexico whiptail as “a species consisting entirely of good friends and roommates.”

“Our understanding of same-sex sexual behavior in animals has really shifted from when I was a queer youth in the ’80s,” said Karen Warkentin, a professor of biology and gender and sexuality studies at Boston University. In the past, Warkentin added, information about queer biology was “actively suppressed,” and scientists were discouraged from studying it. Today, however, many scientists conduct research without these biases, opening the door to a truer understanding of biology.

Take the common name of the mourning gecko, an all-female parthenogenetic species native to Southeast Asia. According to Reptiles Magazine, it comes from a clicking sound they make at night; biologists assumed that they were “mourning” over never having a male mate. As if. That clicking, along with head-bobbing, is actually a primary form of communication for mourning geckos. A recent study published in Life Sciences Education showed that biases like this in biology courses impacted queer students’ sense of belonging and career preparation. By erasing the truth of diverse genders and orientations in nature, this bias helps bigots spread the lie that queerness in humans is “unnatural,” an errant choice. It’s reminiscent of today’s book bans, which label queer texts as profane in a homophobic effort to skew how we view the world.

One of the first things that they teach you in a college biology course is that there’s always exceptions to the rule and that nothing ever fits into nice, neat boxes.

But today’s scientists are studying and communicating nature to the public as it is. Caracalas, who has been a lizard lover her entire life, said she discovered that she was a lesbian around the same time she began studying the Colorado checkered whiptail. Observing the lizards in the field brought her immense joy at a formative time. “Biology has been used as such a weapon against (queer people),” she said. “But ironically, one of the first things that they teach you in a college biology course is that there’s always exceptions to the rule and that nothing ever fits into nice, neat boxes.”

Warkentin believes that the New Mexico whiptail inspires the LGBTQ+ community partly because its complex biology has been studied and communicated so effectively by scientists. For me, learning about New Mexico whiptails has not only anchored me more firmly to the high desert landscape we shared that afternoon, but given me yet another example of how the natural world can shatter human prejudices. In short, these lizards have radicalized me.

Miles W. Griffis is a writer and journalist based in Southern California. He writes “Confetti Westerns,” a serial column at High Country News that explores the queer natural and cultural histories of the American Southwest.