The Senate Committee on Foreign Relations convened for a hearing in D.C. yesterday on a piece of legislation aimed at improving global responses to future pandemics: the Global Health Security and Diplomacy Act.

The hearing focused on how the U.S. should approach future involvement with the World Health Organization (WHO), if alternative organizations should be involved, how China’s lack of transparency in the pandemic and previous epidemics should be addressed, and other practical measures, such as early warning and universal data tracking systems, that the U.S. should take to ensure coordination between countries on an international level.

Testimonies were also heard from: James L. Richardson, Director of the Office of Foreign Assistance; Garrett Grigsby, Director of the Office of Global Affairs; and Chris Milligan, Counselor for the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Sen. Cory Gardner (R-CO), a member of the committee, was notably absent from the discussion of the Senate bill–although he did attract attention for tweeting in the morning about his support for DACA and Dreamers, despite his previous pushback against them.

One thing both the senators and the panelists could all agree on was their disappointment in China’s response to COVID-19.

Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) expressed his concern about China’s corruption.

“We are not sounding the alarm enough. We are seeing the authoritarian regime of China working against our country, from currency manipulation to corporate espionage and stealing secrets,” said Booker. “…But now, in the nature of a pandemic, it is chilling to see that their actions, and what they are doing, is putting lives in our country at risk.”

Booker also advocated for a U.S. role in abolishing “wet markets” (markets selling live wildlife for human consumption) around the world. Wet markets appear to have been responsible for the current pandemic as well as the SARS epidemic.

Richardson also attacked China’s method of foreign relations.

“When you look at [China’s] approach to foreign assistance generally, they have a very mercantilistic, very strategic approach to all of what they do,” said Richardson. “…And I think it does set up a very great dichotomy between, if you want to go with China and accept that type of assistance, you’re gonna go backsliding on your governance and your transparency.”

According to Richardson, China’s nationalization of PPE production and exportation of face masks based on political favor are examples of China’s approach to foreign assistance.

Grigsby, who heavily criticized China as well as the WHO’s praise of China’s response to COVID-19, acknowledged President Trump’s announcement of U.S. withdrawal from WHO, but spoke of possible WHO reforms that the U.S. could help influence, which immediately drew the ire of Ranking Member Sen. Bob Menendez (D-NJ):

“How does the United States expect to influence other members to achieve reform of the WHO if it has relinquished its seat at the table?” Menendez asked.

After a tense exchange between Grigsby and Menendez, and an assurance from Grigsby that an alternate organization such as the global fund could work in tandem with WHO, Menendez replied with, “I appreciate your lengthy answer, which is a non-answer as far as I’m concerned.”

Menendez was not the only swenator who vocalized a difficulty with extracting an answer from the panel.

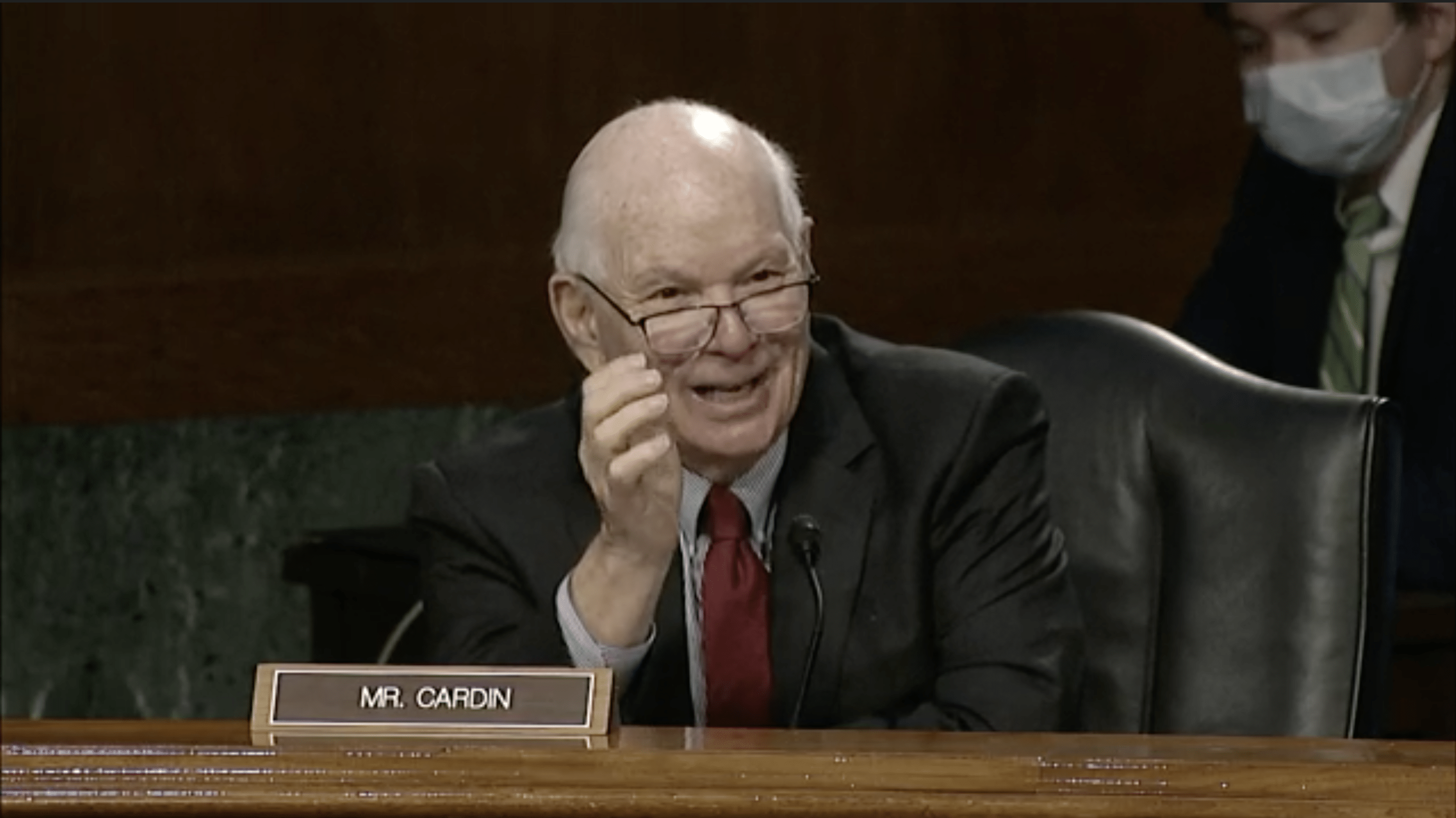

Chairman Sen. James E. Risch (R-ID), Sen. Ben Cardin (D-MD), and Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT) all expressed their frustration at not receiving a straight answer from the panel in response to their direct questions.

The issue of whether to advocate for the U.S. remaining as a member of WHO, and using its influence that way to encourage reform, versus whether to stand with Trump’s decision to withdraw and hold a withdrawal of funding over WHO as an incentive for reform, was a source of much contention.

Sen. John Barrasso (R-WY) suggested that, given the repeated mistakes of WHO, the U.S. should withhold funding to WHO to push for reforms.

“I think we have a lot of leverage, ’cause if you say you want the funding restored, you want us to come back and engage, then give us the kind of credibility and engagement that is necessary,” Barrasso said.

Murphy rejected this idea of using leverage for reform, stating that the U.S. will have much less of a say if it isn’t a member of WHO.

“The idea that we’re going to try and affect WHO reform through the [Group of Seven (G7)] is a new one,” said Murphy. “Can we at least just stipulate, for the time being, that it is harder for the United States to impact reform at the WHO if we are not a part of it, rather than a part of it? It might just be good for us to stipulate that, other or not you’re going to try to pursue reform through the G7 or not.”

According to Grigsby, the G7–a group of seven of the most influential developed nations in the world–holds power as the most generous donors to WHO.

“There is one country that’s desperate for the U.S. to leave the WHO, and that’s China,” continued Murphy. “China is going to fill this vacuum, they are going to put in the money that we have withdrawn and even if we try to rejoin in 2021, it’s going to be under fundamentally different terms, because China will be much more influential because of our even temporary absence from it.”

Grigsby pointed out that the U.S. has been the most generous donor to the WHO.

WHO, Sen. Tim Kaine (D-VA) acknowledged, has its fair share of problems. But Kaine cited the League of Nations and the UN as an example that, while international organizations are in his words “enormously frustrating,” the world is better off with the U.S. being a part of them.