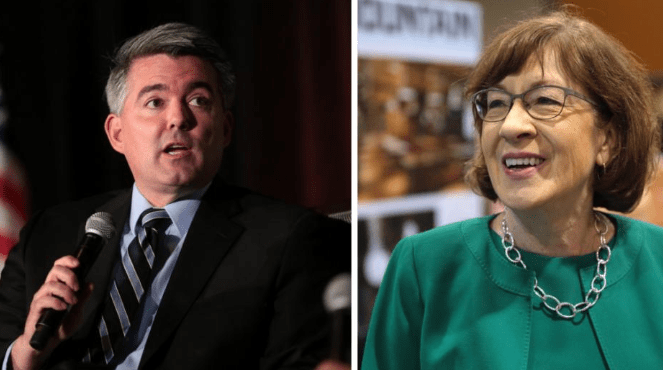

Colorado Sen. Cory Gardner, who’s one of the most vulnerable Republicans in the U.S. Senate, announced yesterday that he would not vote for more impeachment witnesses, including John Bolton.

As Gardner was officially siding with Trump, Maine Sen. Susan Collins, who’s also atop the list of vulnerable Republicans, continued to act as though she was on the verge of approving Bolton and possibly other witnesses.

Despite their different stances on the impeachment trial, Collins and Gardner both come from states that voted for Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump (Colorado went for Clinton by 4.9%, and Maine by 3%.).

This sets them apart from other vulnerable Republican senators (Iowa’s Joni Ernst, Arizona’s Martha McSally, North Carolina’s Thom Tillis), who all represent states that backed Trump in 2016 (Iowa by 9.4%, North Carolina by 3.7%, Arizona by 3.5%).

So you might think that Gardner and Collins would mostly vote together, especially on key legislation.

But that’s not necessarily the case. Even though Colorado is even bluer than Maine, at least based on the 2016 election, Gardner generally votes to the right of Collins in the Senate.

Overall, Gardner votes with Trump 89% of the time, Collins 67%.

Here are some sample votes:

Gardner opposed a Senate resolution last year that would have invalidated Trump’s emergency declaration, allowing the president to use Pentagon funds for the border wall. Gardner’s vote earned him an un-endorsement from The Denver Post.

Collins voted yes, in opposition to Trump.

Gardner cast a losing ‘yes’ vote on a bill in 2018 that would have banned abortion after 20 weeks. Collins joined 51 senators in voting ‘no.’

On a vote to allow Trump to weaken the Affordable Care Act by selling so-called junk insurance, it was the same story, with Gardner voting with Trump and Collins against the president.

In a vote on much-criticized judicial nominee Sara E. Pitlyk, Gardner voted yes, Collins no.

Those are just a few examples of a voting pattern that was topped off yesterday with Gardner’s promise not to vote for more impeachment witnesses.

Political observers in Maine caution against calling Collins a true moderate, however.

“If you get into the weeds of Collins voting record, people will tell you she’s not as moderate as she likes to claim and as her voting record shows,” Brian Duff, an associate political science professor at the University of New England told the Colorado Times Recorder. “She picks and chooses her spots to vote. But I am very comfortable saying, compared to the rest of the Republicans in the Senate, she’s more of a moderate. Her vote [opposing the repeal of] Obamacare, that was a genuine break with her party. She is more moderate, but the Republican Party has moved to the right.”

Whether or not you call Collins a moderate, she is less of a Trump loyalist than Gardner, even though they face similar political terrain in November’s election.

Collins must see the results of the last midterm election as scary, just as Colorado’s 2018 tally looks bad for Gardner. Maine Democrats, motivated by Trump, voted in high numbers, and independents broke Democratic in the midterm. Ditto in Colorado.

So why is Gardner more pro-Trump than Collins?

Maine Might Be Bluer Than Colorado

The political makeup of Maine looks like Colorado’s, but Maine has more Democrats, while Colorado has more unaffiliated voters who act like Democrats. But, again, Hillary Clinton won by a greater margin in Colorado than she did in Maine.

About 33% of Maine voters are registered as Democrat, 27% as Republican, 4% as Green, and less than 1% a Libertarian, according to 2018 statewide voter registration data reported by the Portland Press-Herald. About 35% are unaffiliated, meaning that unaffiliated voters are the largest voting bloc. And Maine has rank-choice voting, meaning, for example, that Greens who list the Democrat as their second choice could put the Democrat over the top in a close election.

In Colorado, 40% of voters are registered as unaffiliated, versus 29% Democrat and 28% Republican, as of the end of last year.

So you might think Collins has more of a political reason to lean left, but polls show many of Colorado’s unaffiliated voters are repelled by Trump as much as Democrats, making the situation in both states comparable.

Gardner Is Locked in With GOP Senate Leaders

Part of the reason Gardner has remained locked down as a partisan Republican, even as his popularity has sunk in Colorado, is that from 2016 to 2018, Gardner led the National Republican Senatorial Committe, which is responsible for electing Republicans to the U.S. Senate.

Gardner was not only part of the Senate leadership team, but his fundraising duties brought him close to high-powered GOP funders nationally. Gardner remains on the Senate leadership to this day, as deputy whip.

Gardner Can Even Less Afford to Lose Any Republican Votes

The conventional wisdom in Colorado appears to be, Gardner can’t win if he opposes Trump, mostly because he can’t afford to lose any Republican votes—much less face a primary—in such a blue-leaning state.

“I think he can win with Trump,” Dick Wadhams, a former chairman of the Colorado Republican Party, told the Colorado Sun. “I don’t think he can win without Trump.”

But Collins faces pretty much the same dynamic, even though historically New England Republicans were known to be truly moderate.

“Increasingly the Republican base in Maine is like the Republican base elsewhere in the country,” said Duff, pointing to the impact of a recent GOP governor. “In that way, Susan Collins is out of step with the Maine Republican Party. It’s tough for her, because Republicans are a minority in the state.”

“She’s given the Republican base plenty to be happy about,” he continued. “She voted ‘yes’ on Kavanaugh. That was a really important vote. She voted yes on the tax bill, which was incredibly important to the Republican elite. She’s done enough to keep Republicans happy.”

Bottom line, Collins seems to be hoping that her moderate image will bring her enough votes to win, while Gardner appears to be banking on some voters possibly warming up to Trump, and, more importantly, many others ticket-splitting, based on the economy and a perception that Gardner is working for Colorado.

Both candidates will likely try to steer the debate to the economy, hope for an unpopular Democratic presidential nominee, and look for openings to break or embrace Trump.

Gardner Is More of a Career-Long Hard-Right Republican Than Collins

While mostly loyal to her party, Collins has been less of a hard-right Republican throughout her career—in contrast to Gardner, who’s been hard-right going back to his days in the U.S. House, and the state legislature before that.

Unlike Collins, Gardner rode his way into Congress by waging a long war on Obamacare. He built his early political career by opposing abortion, even for rape and incest. He’s been a denier of global warming. And more.

Two Vulnerable Senators, Two Different Political Strategies

The impeachment has cast a spotlight on both Gardner and Collins.

“This impeachment trial could not come at a worse time for Susan Collins,” said Duff. “She worked very hard to find a thoughtful, moderate path through it. A vote to let Trump off the hook for this would be infuriating to most Mainers, and a vote to convict him would be infuriating to the Republican base.”

Some are saying the same thing about Gardner. The two senators appear to be, at least for now, in the same boat.

“Two of the most contested Senate races display these two very different strategies,” said Duff. “It will be interesting to see which one works best.”