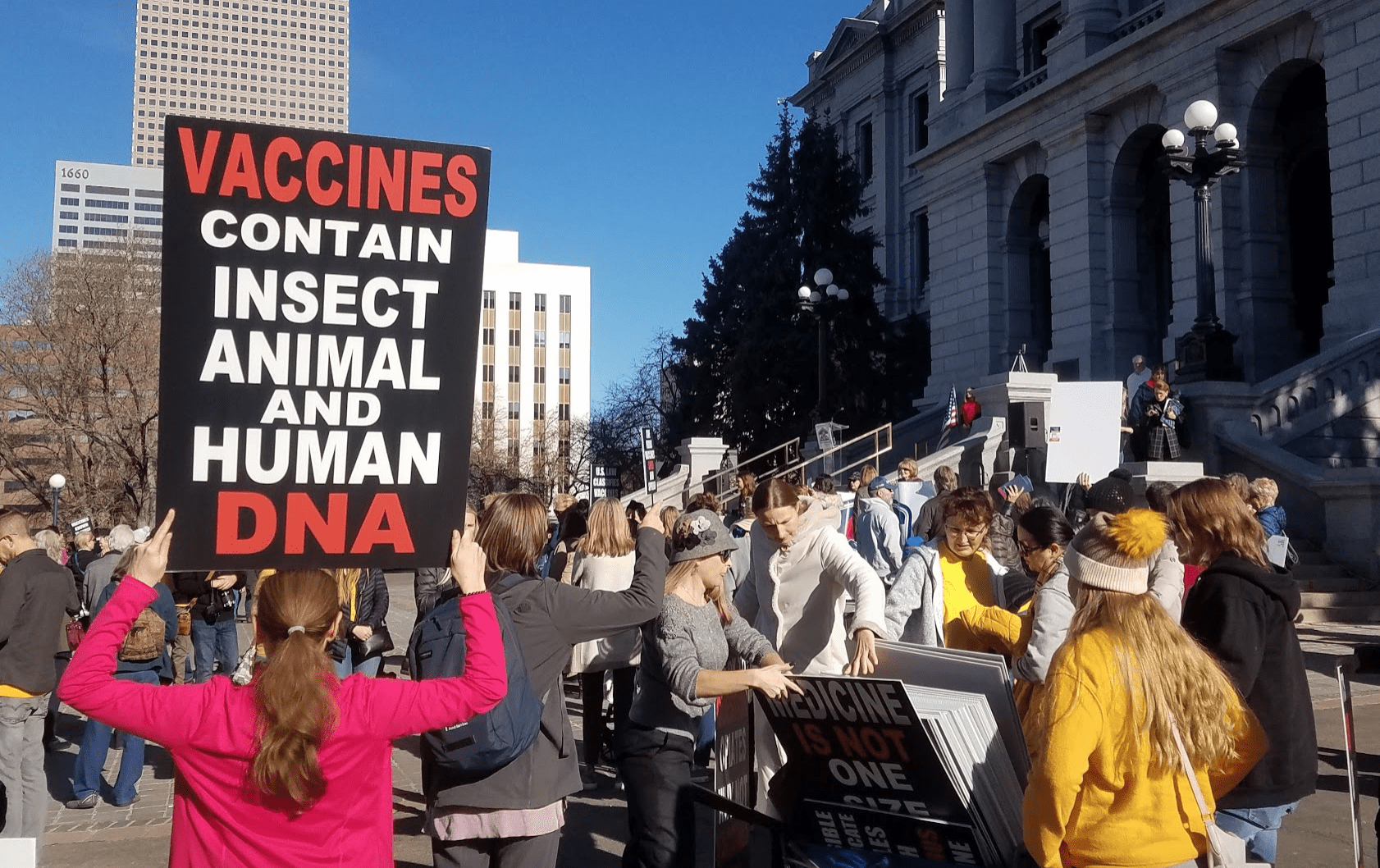

After Tuesday’s vaccine-oriented rally in front of the Colorado State Capitol, a few parents and some of their school-age children filled a committee room in the ornate building’s basement for a town-hall meeting, organized by state Rep. Dave Williams (R-Colorado Springs), to discuss his proposed legislation, called the Vaccine Consumer Protection bill.

“If families believe that [vaccination is] a benefit to them, then so be it – take it on yourself,” Williams said, summarizing his bill, which has yet to be released. “But if there are parents and families that know of vaccine injuries that have occurred and they don’t want to have that risk, then that’s fine, too.”

Williams said the proposed legislation would require health care providers to give information about vaccines to patients when requested and report adverse vaccine-related events.

He added that the bill would outlaw government discrimination against those on delayed vaccine schedules or those who outright refuse vaccination.

While the World Health Organization (WHO) does acknowledge there have been some rare cases of adverse side effects associated with vaccines, its page on common vaccine misconceptions completely dispels the idea that vaccine-related health issues are at all common or widespread.

With respect to risks of not vaccinating, Colorado has one of the lowest immunization rates in the country, with only 87 percent of the state’s kindergarteners having received the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine during the last school year. A vaccination rate of 90 to 95 percent is required to achieve herd immunity, meaning that enough of the population is immune in order to prevent the spread of the disease, particularly among those who are unable to receive certain immunizations, like infants.

RELATED: Republican Lawmakers to Host Anti-Vaccination Summit at Colorado Capitol

A press release from Medical Autonomy Colorado, an organization skeptical of vaccines, said the bill will include provisions to “increase disclosure of ingredients, side effects and risks,” and “add liability on manufacturers for undisclosed injuries.”

Colene Elaine, a consultant for Medical Autonomy Colorado who worked on the bill, said it transcends partisan bickering.

“It’s not a Republican thing and it’s not a Democrat thing,” she said. “If anything, it’s more of a Democratic platform with consumer rights and consumer protection – and it’s a Republican bringing the bill to the table for us.”

Although most of the town hall (excluding children) was populated by white mothers, the group did seem to cut across some traditional socio-cultural lines.

“We have Christians, we have atheists; we have Hindus, we have Muslims; we have straight, we have LGBTQ,” Elaine said. “It’s awesome that everyone works together in such a unified way.”

The prevailing sentiment was to push the anti-vaccination agenda harder.

“All of last year we were on defense,” said Rep. Mark Baisley (R-Teller County). “They came at us with their progressive aggression saying we want to assert this on you as the force of government.”

Last year, legislation to modernize school vaccine requirements caused panic in the Colorado anti-vaccine community when it passed the state House before dying in the state Senate.

The bill, which would have required submission of a form to opt-out of state immunization requirements, was introduced by Rep. Kyle Mullica (D-Northglenn), a nurse. It got a yes from every Democrat in the state House except Rep. Brianna Titone (D-Arvada), Colorado’s first openly transgender state legislator and a frequently-lauded martyr at Tuesday’s town hall.

“Here is a case where we’re standing up and being on the offense ourselves,” Baisley said. “It’ll rock them back on their heels a bit and they’re going to have to defend their position for a change.”

His assertion that it was better to be on the legislative offense going into 2020 was well received.

Panicked Parents

Some of the town hall’s attendees were panicked. Several characterized themselves as “refugees” from California’s recent pro-vaccine legislation. Others said their children were essentially without healthcare given the scarcity of pediatricians willing to treat unvaccinated patients.

The idea that Child Protective Services could separate children from parents who refused to vaccinate came up repeatedly. It was an effective rhetorical point and emblematic of the event’s broader sentiment — even though no such proposal has been seriously considered in Colorado.

Still, Williams managed to keep the event surprisingly upbeat and free of rancor.

Although Williams was far from anti-vaccine, he was also entirely unalarmed by the prospect of Colorado’s vaccination rates dropping.

“If the overall rates go down as a result of individual family choices, so be it,” he said. Williams characterized his bill “as sort of a free-market approach.”

“This is something where we should be able to have a good dialogue in the open market of ideas and the best idea and the truth will usually win out,” he said.

Pam Long, a board member at another vaccine-skeptic organization called the Colorado Health Choice Alliance, also worked closely with Williams on the bill. Williams, who characterized himself as a non-expert, would defer to her and Elaine often.

“I’m a one-issue person,” said Long, a former US Army medical service corps officer who claimed her son “is injured for life from a vaccine and will never live” independently.

Long said most American children born today will receive 70 vaccines before they turn 18.

That’s “more vaccines than I received as an army veteran deployed world-wide to third-world countries where the water and the food are not safe to eat and drink,” she said.

“I have that background in risk assessment,” Long said, “and what you’re going to see with this bill is that we’re actually bringing to the public that there are actually risks to vaccination.”

While Long also acknowledged that there are risks to not vaccinating one’s children, she said the risks associated with vaccinations are woefully understated by the medical community – a point the WHO would rebuff.

Williams said he and his wife decided to vaccinate their children, but on a delayed schedule – a move the Center for Disease Control characterized as risky.

“I think what we wanted to do was just make sure that we’re completely understanding of the risks and the benefits,” he said. “At the end of the day, we didn’t feel it was appropriate to be vaccinating our child at a very young age with the schedule they have now.”