As 2018 draws to a close and we begin to reflect on what we probably all agree was another strange year, I’d like to offer this as an emblem of where we’re at: progressive women along Colorado’s Front Range are going around destroying neo-Nazi propaganda that appears to have been strategically placed near — wait for it — Pokemon Go waypoints.

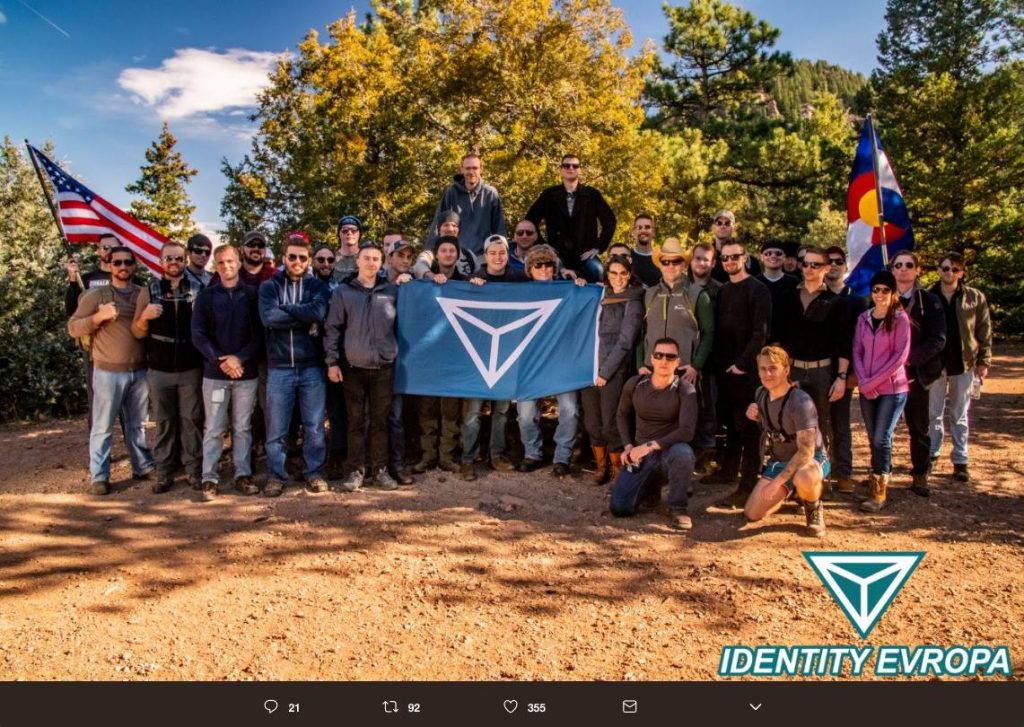

The propaganda is being disseminated by the recently formed white nationalist group Identity Evropa, which in recent months has been ramping up activity in the Rocky Mountain region. They gained notoriety after helping organize 2017’s Unite the Rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, where a counter-protester was murdered, and recently held a rally in Denver’s Civic Center Park.

Their goal? Lure young white men with conservative leanings into the white supremacist fold to revitalize the image of their movement and bring it into the mainstream.

The group, which leaders have referred to as a “fraternity,” is especially active on college campuses, where it hopes to attract well-educated and clean cut men – not, as their founder Nathan Domingo put it in an interview with the Daily Beast, “some uneducated redneck living in the bayou somewhere.”

Put bluntly, Identity Evropa wants to make Nazis cool again. They have a podcast. They go hiking. And they’re apparently trying to catch ’em while they’re young by putting up propaganda where young eyes will see it – at Pokemon Go waypoints and college campuses.

But are they any match for Colorado’s so-called resistance movement?

Since the 2016 election, Indivisible and other newly formed groups of progressive activists, which are largely comprised of suburban women, have been using social media to plan rallies, share volunteer opportunities, and flood congressional offices with phone calls. Now, they’re using it to hamstring Identity Evropa’s propaganda campaign.

That propaganda includes stickers and flyers with their name and logo, sometimes accompanied by white pride slogans and images of classical European sculpture, which have become increasingly common in white supremacist circles. Identity Evropa then shares photos of the new propaganda on their Twitter page, along with the name of the city or college campus where it was posted.

It doesn’t take long before Indivisible and their allies share this information on their social media pages, where one of their members is sure to recognize the exact location and either go remove the propaganda themselves or send someone they know in the area to do so.

On one occasion, Identity Evropa posted photos of new stickers in Arvada. The photos were shared in local resistance groups, where they caught the eye of an Arvada resident who recognized the water tower in the background. She asked me not to use her name, because, as she put it, “these clowns are not very nice.” I’ll refer to her as Kim.

On one occasion, Identity Evropa posted photos of new stickers in Arvada. The photos were shared in local resistance groups, where they caught the eye of an Arvada resident who recognized the water tower in the background. She asked me not to use her name, because, as she put it, “these clowns are not very nice.” I’ll refer to her as Kim.

Kim told me that their groups have become fairly tight-knit since the 2016 election, making it easy to identify members who live near Identity Evropa’s most recent target and can quickly go out and remove whatever they’ve put up.

Imagine a game of whack-a-mole between white nationalists and progressive women. The progressive women appear to be winning.

“We’re crowdsourcing it,” Kim told me. “It’s not like we have secret handshakes or anything, but most of us know most of us. Some of us are neighbors, some are political activists, and some of us are interested in third-party activities. Some of us go to church together.”

“I’ve made a lot of interesting friends since 2016,” said another woman, who also preferred I not use her name due to privacy concerns. I’ll call her Sadie.

Sadie has been taking down propaganda in Denver’s suburbs, including Wheat Ridge and Arvada, and at Red Rocks Community College.

Another woman who I’ll refer to as Kirstin, who’s active in Indivisible, said she started sharing information about Identity Evropa with her group after being notified of their presence by Colorado Springs Anti-Fascists. Kirstin has taken down stickers at the University of Colorado campus in Boulder.

An activist with Colorado Springs Anti-Fascists, under the pseudonym Rosa Luxembourg, told Westword’s Michael Roberts that the group is looking into connections between Identity Evropa and CSU fraternities, noting that Unite the Right protester Clark Canepa is a former CSU student with connections in Greek life.

“Given the inherent classicism, racism and misogyny of ‘Greek life,’ it makes sense that Identity Evropa (who have a reputation as ‘trust fund Nazis’) would try to recruit frat bros,” she told Westword.

“It’s just so insidious, and we don’t realize it could reach our children,” said Kirstin, who’s a mother. “This is not an ideology that hangs out in these dingy recesses of our culture. It is front and center and it is trying to look legit. They’re doing a PR campaign right in front of us.”

But here’s where things get especially weird.

These progressive groups believe Identity Evropa is using augmented reality games like Pokemon Go to identify places to place propaganda and recruit youngsters.

How did they arrive at this conclusion?

As it turns out, Identity Evropa’s logo is extremely similar to that of a game called Ingress, another augmented reality game from Pokemon Go developer Niantic. The games both use certain geographical locations – like notable landmarks in public parks and on campuses – within the game.

So, for example, a “gym” in Pokemon Go, where players can battle their pokemon, might be located at a statue in a public park. It then becomes a gathering point for the gamers — and sees increased foot traffic as a result.

Once the Indivisibles and their allies noticed the connection between the logos, they verified that much of the propaganda was placed near these geographical waypoints, and it made it easier to track it down, according to multiple women within the groups.

Identity Evropa spokesman Sam Harrington told the Colorado Times Recorder that “similarities between our logo and that of the game in question are purely coincidental,” but didn’t address the charge that they’re placing propaganda in key Pokemon Go locations.

The game developer Niantic didn’t respond to an email asking if it plans to address Identity Evropa’s apparent use of their augmented reality games.

“It’s really important for parents to know,” said Sadie, who’s also a mother. “People need to teach their kids to be anti-racist. I’m coming to the realization that it’s important. I used to not talk to my kid about ugly stuff like that, but she knows that I pulled down those stickers and why it’s important.”

“These are the kinds of images that sneak in and become subversive and become implicitly acceptable,” said Kim, who shared Sadie’s concerns about Identity Evropa’s apparent tactic of recruiting young people. “Children are a vulnerable community.”

“Promoting hate turns into hate crimes,” Kim added.

Hate incidents are, in fact, on the rise. According to the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), anti-Semitic incidents tripled in Colorado over a two year period, an increase that mirrors nationwide numbers.

A similar story was published this morning by Westword’s Michael Roberts.