How Cory Gardner's War Against Obamacare Propelled Him to Power--and Is Now a Driver of His Likely Demise

At his first campaign rally for U.S. Senate, on a snowy day in 2014 at a Denver lumber yard, Cory Gardner warned that Obamacare was “destroying this country.”

The words may sound harsh today, but they came easily to then-Congressman Gardner. His attacks on the country’s new health care law were a centerpiece of his first successful run for Congress four years earlier, when he raised the specter of 17,000 new IRS agents “storming” America in search of Obamacare cheaters and of the health care law failing because people just wouldn’t sign up.

Torching Obamacare in interviews and ads, Gardner cruised into the House in 2010 and edged his way into the Senate four years later.

But in an irony that’s lost on no one who’s followed Colorado’s Republican senator over his ten years in Washington, Gardner’s long war against the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is now a driver of his likely downfall.

Gardner Entered Congress Stoking Anti-Obamacare Tea Party Wave

Gardner was first elected to the U.S. House in the Republican Tea Party wave of 2010, when he defeated Democratic incumbent Betsy Markey in a Republican-leaning district.

It was the first midterm election after President Barack Obama took office, and newly organized Tea Party groups grabbed headlines across the country by confronting Democrats about Obama’s newly passed ACA.

In the summer before the election, at town hall meetings across her district, Markey faced rooms packed with constituents angry about Obamacare.

“Betsy would go into these meetings, and she held her ground, but we would have people literally scream at her for two hours about the ACA,” Markey’s then-campaign manager, Anne Caprara, told the Colorado Times Recorder. “She took it, but it was hard.”

“Gardner did everything in his power to gin up the Tea Party to attack Betsy at those town halls,” said Caprara, adding that she finds it “incredibly ironic that now he’s running for re-election to the Senate” and hasn’t held a town hall meeting in over two years.

Gardner’s 2010 and 2014 campaign manager, Chris Hansen, didn’t return an email seeking comment, but Gardner said at the time that voters were genuinely “outraged” at Markey for supporting the health care law, which could “very well” come down to her vote in particular. He said Markey’s constituents wanted somebody in Congress who “actually represents them instead of just does the party’s work.”

Gardner ridiculed the congresswoman for drawing praise from Obama himself for her ‘yes’ vote on the legislation.

In March of 2010, after Markey voted for the ACA, Gardner wrote in a fundraising appeal that, if elected, he would repeal the “trillion-dollar healthcare takeover.”

“Betsy Markey is out of step with the 4th Congressional district to be in lockstep with the Washington lobbyists who have been the main sponsors of this legislation,” wrote Gardner at a time.

Caprara says Markey was trying to find a practical approach to address a health care crisis, which, among other things, included 16% of Coloradans who had no health insurance.

“Cory made a big deal of saying, ‘It’s not that I don’t want to protect people with pre-existing conditions, it’s just that this whole health care situation will be bad for people,” said Caprara.

“Gardner played this game constantly with us.” said Caprara. “He cared about one thing, and that was winning.”

As Congressman, Gardner Remained at War with Obamacare

After beating Markey and entering the U.S. House, Gardner kept his promise, voting multiple times to repeal the ACA and requesting that his Colorado House district receive a waiver to opt out of the law.

Cory Gardner at 2013 House Hearing with HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius testifying about the problems with the release of the Healthcare.gov. Cory Gardner starts at 3:02:51 on the CSPAN video.

Gardner even threatened in 2013 to shut down the federal government unless Obamacare funding was removed from the budget bill. And, ultimately, as 9News later confirmed, Gardner voted “in line with the Republican strategy that led to the government shutdown” over Obamacare funding.

“I want to do anything and everything I can to stop Obamacare from destroying our health care, from driving up increases in costs,” Gardner said at the time when asked about whether he’d favor shutting down the government to defund Obamacare, resulting in the death of the law. “Whether that’s through the continuing resolution, I want to defund everything that we can….”

Gardner’s Senate Campaign Centered on Blaming Udall for Obamacare

With his unassailable record opposing Obamacare, and with Democrats again staring at a red wave in the 2014 election, Gardner announced in February of that year that he was challenging Mark Udall for Colorado’s Senate seat.

And what was at the heart of Gardner’s campaign-origin story, his reason for running? Obamacare.

Gardner said he’d thought previously about running for Senate, but he rejected the idea until he received notice that his own health insurance plan had been cancelled due to Obamacare.

“I thought about reconsidering running for the U.S. Senate, but it really picked up last year when we received our healthcare cancellation notice,” said Gardner at the time in explaining his change of heart in running for the U.S. Senate.

“Mark Udall voted for Obamacare,” Gardner told Fox 31 Denver the week after he announced his candidacy. “It’s destroying this country.”

Even the national debt was linked to Obamacare.

“We need to start addressing the issue of our national debt by repealing Obamacare, which adds hundreds of millions of dollars in debt to our economy,” Gardner said during the campaign.

In interviews, Gardner portrayed Udall as somehow the “deciding vote” in passing Obamacare and as responsible for “Barack Obama’s bill that Mark Udall passed.“

“When Mark Udall voted for Obamacare, he promised us, if we liked our health care plan, we could keep it. But you know how that worked out. I got a letter saying that my family’s insurance plan was canceled,” said Gardner in one ad as he famously flashed his Obamacare letter in front of the camera. “335,000 Coloradans had their plans canceled too. Thousands of families saw their healthcare premiums rise. More cancellations are on the way. You might have one of those letters in your mailbox right now. I’m Cory Gardner. I approve this message. Let’s shake up the Senate.”

Fact checkers, like 9News, pointed out that “it’s true that millions of people with individual coverage got cancellation notices because their old plans didn’t meet the standards of Obamacare…. But getting one of these notices is not the same thing as losing insurance.”

In its critique of a Gardner ad, 9News explained:

By federal law, when they cancel a plan, insurance companies have to offer you an alternate plan if they want to stay in business. Of course, some of those alternate plans were more expensive and that caused trouble for people.

But this ad is trying to make you believe that all those people just became uninsured, which is just not the case.

Bottom line: renewals were offered to the vast majority of people whose insurance policies were canceled, and new policies were offered to all.

This didn’t stop Gardner from deftly presenting himself as an aggrieved citizen, accusing Udall of possible “abuse of power” for pushing back on the figures and claiming that he was forced to replace his own family’s insurance policy with an Obamacare plan that was “more costly, inferior,” going from a premium of $650 to $1,480 per month.

But, to the consternation of multiple journalists, he never provided the details of his own plan (as in, what it covered or the amount of its deductible) so that the public could verify his statements and compare the benefits of his Obamacare policy and his previous plan. A premium $650/family of four was absurdly low.

“Sometimes the candidate doesn’t answer the question,” said then Denver Post Politics Editor Chuck Plunkett after Gardner refused to answer questions about his insurance plan. “That also tells you something about the candidate the voters should know.”

So even Gardner’s personal story about Obamacare, like his other ferocious allegations about the law, was unverifiable at best, wild exaggeration or flat-out misinformation at worst.

In 2014, 60% of Coloradans Opposed Obamacare

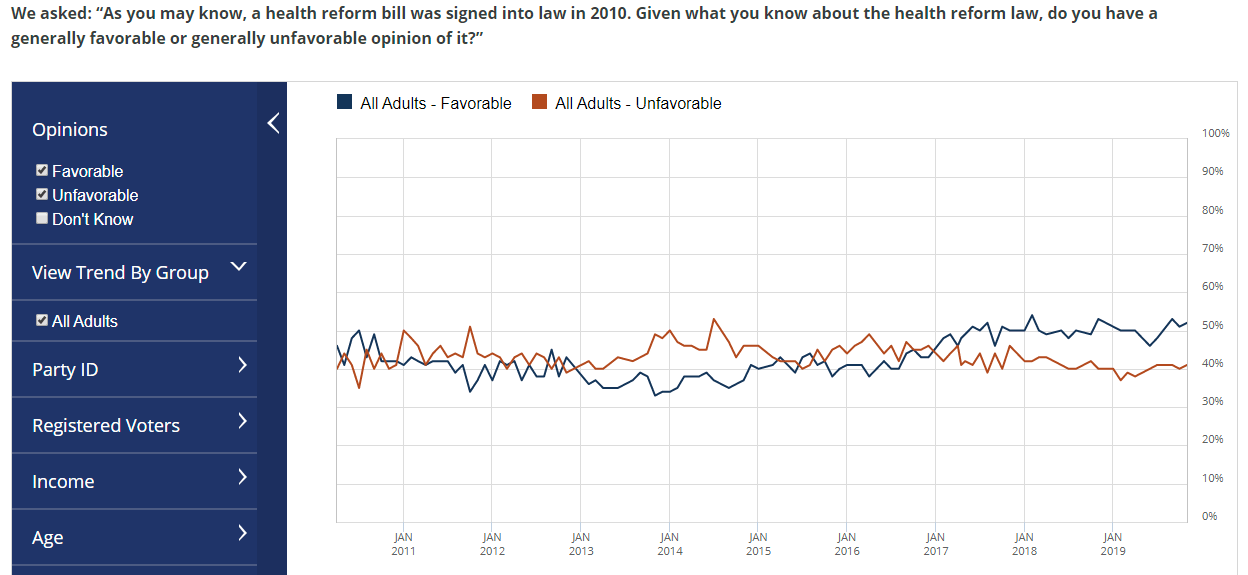

Throughout his 2014 Senate campaign, at a time when Coloradans opposed Obamacare by a 60% to 37% margin, Gardner continued promoting himself as the poster-child victim of the national healthcare law. It needed to be killed, he said, by any means available.

And as he would continue to do in the coming years, Gardner did not offer alternatives that protected people with pre-existing conditions, and he provided no plan to provide health insurance coverage to Coloradans who would gain it in the coming years as Obamacare slowly reduced Colorado’s uninsured rate from 16% to 6%.

But, still, riding the anti-Obamacare and general anti-Obama sentiment that prevailed at the time, Gardner won a narrow victory over Udall in November, 2014, and became Colorado’s senator.

“Obamacare was so unpopular at the time,” Jim Carpenter, who advised Udall in 2014, told the Colorado Times Recorder. “And that’s why it was a smart short-term strategy for the Republicans. It just wasn’t working for the Democrats to say, ‘Let’s fix [the ACA’s] flaws.’ That was frustrating. But not much was working in 2014, frankly.”

“It’s part of the story of Obamacare itself,” continued Carpenter, who’s the co-founder of Freestone Strategies and a longtime political strategist in Colorado. “You campaign on healthcare reform, which President Obama and the Democrats did [in 2008], and you implement something that’s really big. It doesn’t work perfectly.”

“So it was easy to take a political shot at Obamacare; Cory Gardner didn’t have to be substantive or particularly thoughtful,” said Carpenter. “He could just take the political shot. And a lot of people lost their seats both in 2010 and then in 2014, in part for their support of this.”

Thumb Down from McCain, Thumb Up from Gardner

During Gardner’s first year in the Senate, the U.S. Supreme Court seemed poised to strike down Obamacare, and Gardner, who’d quickly been elected to the Senate’s Republican leadership team, promised that Republicans would have an ACA replacement plan “ready to go” if the high court overturned the law.

But the Supreme Court upheld the ACA in 2015, leaving the status quo in place. That was until Donald Trump’s surprise victory in 2016.

When the GOP suddenly controlled the White House along with the House and Senate in 2017, they had the power to kill Obamacare.

That’s when the climate Gardner faced around the ACA began to change in a big way.

In April 2017, for the first time since Gallup began polling on the topic, a majority of Americans approved of the national health care law, with a major leap in favor-ability occurring in the previous five months as more attention was focused on what would be lost if Republicans succeeded in repealing Obamacare. This came even as Gardner continued to call Obamacare a “disaster for the American people.”

For the previous seven years, GOP votes to kill the ACA had become so ritualistic as to be ignored. But now with increased scrutiny of the ramifications of losing Obamacare came increased support for the law, under which 500,000 people in Colorado now got health insurance.

In May 2017, the Republican-controlled House passed a bill to repeal and replace the ACA. It would have left 22 million Americans without health insurance in the ensuing ten years, according to the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO). About 400,000 Coloradans would lose their coverage within five years, experts predicted.

Gardner, who had promised to soften the blow on folks who’d lose health insurance under the legislation, was one of 13 GOP senators assigned to draft the Senate version of the House bill. Gardner used this role, even though it was never clear what he actually did, to position himself as protecting the Medicaid expansion under the ACA, which Colorado had successfully adopted in 2013 under Gov. John Hickenlooper (D-CO), extending coverage to some 400,000 Coloradans. Upending the Medicaid expansion population would arguably have been the most visible disruption under the three GOP repeal bills, and Gardner earned headlines suggesting he was not completely hostile to Medicaid but instead wanting to put Medicaid on a “glide path” to an eventual rollback.

Gardner also insisted for months that he was undecided on how he’d vote, up until the last morning before the Senate took action on the final bills, and he asked for a second opinion on the CBO estimate that so many millions would be left uninsured.

After much drama, and three measures ranging for outright repeal of the ACA to the narrower “skinny repeal” that was supposed squeak by with a bare majority in the Senate, Gardner voted for everything the party leadership put forward.

The last proposal, the so-called “skinny repeal,” lost thanks to defections from three Republicans, including Sen. John McCain of Arizona, who’d just returned to the Senate after receiving a diagnosis of brain cancer.

Leading up to all three Senate votes, Gardner wouldn’t tell reporters where he stood, but his support for the Obamacare-repeal measures was never seriously considered in doubt, in part, most analysts agreed, due to his leadership position in the Senate, tying him closely to Sen. Mitch McConnell of Kentucky.

Gardner and his fellow Republicans never produced a concrete replacement plan that came close to matching Obamacare’s breadth of coverage and benefits, such as protections for people (over 2 million in Colorado) with pre-existing conditions, provisions allowing young adults (40,000 in Colorado) to stay on their parents’ insurance plans, mandatory preventative care (checkups, mammograms) for 2,519,638 Coloradans who might not otherwise have free access, and more. Gardner repeatedly said he wanted an Obamacare replacement that would lower insurance costs, but studies showed that premiums would increase at a higher rate under the GOP proposals.

And so, by the end of 2017, the seven-year GOP effort to repeal Obamacare died, at least in Congress.

After Failure in Congress, Gardner Backed Trump Efforts to Weaken ACA in Courts

But that didn’t stop Gardner from continuing to attack the health care law throughout 2018 and into 2019 and continuing to back Trump’s initiatives to weaken it, including the president’s order allowing the sale of so-called junk insurance that would skirt the ACA’s guarantee that insurance companies cannot deny coverage to people with pre-existing conditions.

Gardner also appears to support a lawsuit heading toward the U.S. Supreme Court that again aims to kill Obamacare outright. When The Hill newspaper asked Gardner last year his position on the lawsuit, Gardner said, “That’s the court’s decision. If the Democrats want to stand for an unconstitutional law, I guess that’s their choice.” He is not part of a Senate resolution that would force Trump to stop supporting the lawsuit.

Obamacare Now a Liability for Gardner

Gardner, who did not return a call to discuss this article, goes into the election year with the popularity of Obamacare near its highest point since it was enacted, with 52% of adults viewing it favorably.

That’s in contrast a 39% favorability rating for the senator himself, close to its lowest ever.

“In 2014, we were only a few years into Obamacare,” Chris Keating, of the polling firm Keating Research, told the Colorado Times Recorder. “Six more years after that, people are thinking, ‘This is a good thing that young people and people with pre-existing conditions get insurance and that the number of uninsured has been brought down.'”

“We just have a different dynamic this year when it comes to Obamacare,” said Keating.

Keating points out that about a million more voters will be casting ballots this year in Colorado than when Gardner was elected senator in 2014, and most of them are young and unaffiliated—and likely to vote in November. And these voters, ages 18 to 49, support keeping Obamacare by a 2 to 1 margin; people who are 18 to 34 want Obamacare by 70%, said Keating, citing his 2017 Colorado poll.

“You’ve got all these new voters who are coming into this election, compared to the last time Gardner was elected, and they support Obamacare”

– Chris Keating

In addition, Colorado now has more Democrats registered to vote than Republicans.

“Republicans had a five-point advantage in 2014,” said Keating. “That’s 100,000 votes Gardner had in the bank just from that difference. When he goes into this election, it’s going to be plus two [percentage points] Democrats. So Democrats are going to have that in the bank, plus they’ve got the unaffiliated voters. There’s no conceivable path I see for Gardner.”

While Obamacare will likely hurt Gardner, Keating emphasizes that Trump is a bigger problem for him.

“Number one, this election is going to be a referendum with Trump,” said Keating, pointing out that hostility toward Obama himself, not just Obamacare, drove voters to Gardner in 2014. “The number one thing is, Gardner’s association with Donald Trump, and the fact that he has stood by him.”

Republican activists worry about Gardner in the next election, to be sure, but some say, if any candidate can win this year, it’s Gardner, despite voting 90% of the time with Trump.

“I think Cory is going to eke it out; I really do, at this point, I really do,” said longtime GOP operative Dick Wadhams said this month, due to “the quality of candidate [Gardner] is going to be.”

Obamacare Defenders Out in Force

When Gardner used Obamacare to attack both Udall and Markey, you didn’t see progressive activists, or Democratic groups, doing much to defend the health care law.

Today, with surveys showing that the health care issue was a major benefit for Democrats in 2018, most every national development on the Obamacare front (e.g., a court decision, congressional vote, Trump utterance) is met with news releases from Democratic candidates and/or progressive groups and, often, protests in front of Gardner’s office in Colorado. Meanwhile, the anti-Obamacare sirens are mostly silent.

Protect Our Care, for example, is a national coalition that exists to “protect the Affordable Care Act from Republican Attacks,” says spokeswoman Olga Robak.

“Protect Our Care Colorado is here to remind voters in our state exactly where Gardner’s loyalties lie on protecting health care,” said Robak. “And let’s be clear: it’s not with Coloradans, it’s with the Trump administration.”

“Health care was a major issue in the 2018 election and will be again in 2020,” said Adam Fox, Director of Strategic Engagement for the Colorado Consumer Health Initiative, a progressive health care advocacy organization. “Senator Gardner’s consistent efforts to take away Coloradans’ health care despite the outcry from his constituents will undoubtedly be highlighted and on the minds of voters.”

For those who lived through Gardner’s rise to power, it makes sense that the senator’s popularity in Colorado loosely tracks with the inverse of the favorability rating of the ACA. Gardner’s approval stands at about the 39% mark today, down from 48% percent just after he was elected to the Senate in 2015. The inflection point hit around January 2017.

Now, where does Gardner go on Obamacare?

As he launches his re-election campaign, Gardner isn’t standing with his Obamacare letter in his hand and saying the health care law will destroy America, like he did in 2014.

His Senate website still calls for “repealing the Affordable Care Act and replacing it with patient-centered solutions, which empower Americans and their doctors.”

But there are signs that Gardner may try to talk about Obamacare as little as possible.

In a little-noticed change to the “Health Care” section of his new re-election campaign website, Gardner has removed any mention of Obamacare, much less his darkest views about the threat it poses to the country.

Instead, Gardner is trying to tout his goals and achievements in the health care arena, with his campaign website stating that the senator “worked with Governor Polis and the Trump Administration to secure a waiver for Colorado to implement a reinsurance program that will reduce health care costs for hardworking Coloradans.”

But the reinsurance program is actually part of Obamacare, which Gardner still wants to kill. The Republican’s ironic stance led 9News’ Kyle Clark to observe, “Senator Gardner wants to demolish the house, but today he’s claiming credit for helping the homeowners put on an addition.”

Gardner’s Costly Refusal to Try to Improve Obamacare?

Did Gardner try to demolish the house for too long, without perhaps giving renovation a try?

If Republicans had changed directions along the way, and tried to help Democrats fix Obamacare, instead of continuing their campaign to kill it, the issue might not be the liability that it is today, says Carpenter, Udall’s former adviser.

“I think the big mistake Republicans have always made on this is, and a frustration for Democrats, is that they haven’t been able to go in and fix particular pieces of it,” said Carpenter. “No law, particularly something this big, is going to be perfect on day one or on day 100. You have to go in and fix it. And hopefully you have people of good faith working on those things, but we just haven’t seen that in our political process.”

He said that it would have hard, if not impossible, for Gardner politically to join Democrats in making Obamacare work better. But still.

“Gardner has found himself in this spot where he’s advocating to get rid of the whole thing and start over, but it’s just not where people are now,” said Carpenter. “Again, short-term political advantage gets you in trouble down the road. I think Cory has found himself in a lot of those spots now.”

For Gardner, the trouble down the road has arrived.