Republican CU Regent At-Large Heidi Ganahl recently had a brain tumor successfully removed by surgeons at CU Anschutz. Now, she’s using her experience to argue against a proposal to launch a public health insurance option in Colorado in part because it could “endanger miracles like mine.”

Ganahl penned a column for the Denver Gazette last Monday to tell readers about her stint in the hospital a few months ago. Her positive experience with Colorado’s state-of-the-art medical care provides the foundation for her argument against the Colorado Affordable Health Care Option:

“The proposed Colorado Affordable Health Care Option is not the broad solution politicians claim,” writes Ganahl in her column. “With unintended consequences to quality and access, it may force hospitals to eliminate some critical care functions. It may even endanger miracles like mine.”

While public-option legislation hasn’t been introduced yet, it will likely resemble the bill introduced last year, which mandated that insurance companies that sell health insurance to individuals on the state’s Obamacare exchange also carry the public-option plan.

However, according to the two major sponsors of this year’s bill, Sen. Kerry Donovan (D-Vail) and Rep. Dylan Roberts (D-Avon), there will be some notable changes from last year’s legislation.

Roberts didn’t tell the Colorado Times Recorder all of the changes that will be made but did say that this time around, the bill will take longer to go into effect, allowing health care providers, which have been stretched thin during the pandemic, more time to adjust.

“We’re going to allow more time for this to take effect, so that our healthcare providers like our hospitals and our doctors can get through COVID before any new plans go into place or anything like that,” said Roberts. “…We’re going to go through the feedback the healthcare industry folks gave us last year, and incorporate that.”

Ganahl claims in the article that “the legislature’s Colorado Option Plan may cut annual hospital revenues by $1.1 billion more over the next three years,” and that “this could push the system creating miracles—one of the top-rated hospital systems in the country—to a breaking point.”

When asked to respond to Ganahl’s comments, Roberts told the Colorado Times Recorder that “Ganahl is citing a right-wing, conservative think-tank study that isn’t based on any actual legislation. It’s based on a hypothetical model, that I think was done to produce their intended result to cast dispersions on the public option.”

Roberts is presumably referencing the Common Sense Institute (CSI)–of which Ganahl is a board member.

According to CSI, most of the enrollees in the public option, were it to pass, would not be previously uninsured–an aspect of the bill that the think tank sees as a weakness.

But according to Adam Fox, Deputy Director of the Colorado Consumer Health Initiative (CCHI), a non-profit health equity organization, “even before the pandemic, one in five Coloradans struggled to afford their health care costs or went without care altogether,” meaning that even Coloradans who are insured need respite from exorbitant costs.

Fox also told the Colorado Times Recorder that “It’s par for the course that the health care industry says the sky will fall from a policy that will hold them accountable and that seeks to lower health care costs.”

There’s also the potential for the policy to hurt rural hospitals, but Roberts claims there will be safeguards in the bill to protect rural hospitals.

“We put in specific protections into the bill last year–and we will this year–that rural, small, and independent hospitals are not disproportionately impacted; they might actually see a benefit from this bill,” Roberts told the Colorado Times Recorder. “I represent rural Colorado, Senator Donovan represents rural Colorado; we would never introduce a bill that would hurt rural hospitals.”

The benefit from the public option, says Roberts, will come from more people accessing healthcare, contrary to the claim of CSI.

“More people are going to have insurance, and so more people are going to receive medical care,” said Roberts. “So we can actually see hospitals increasing their patient capacity.”

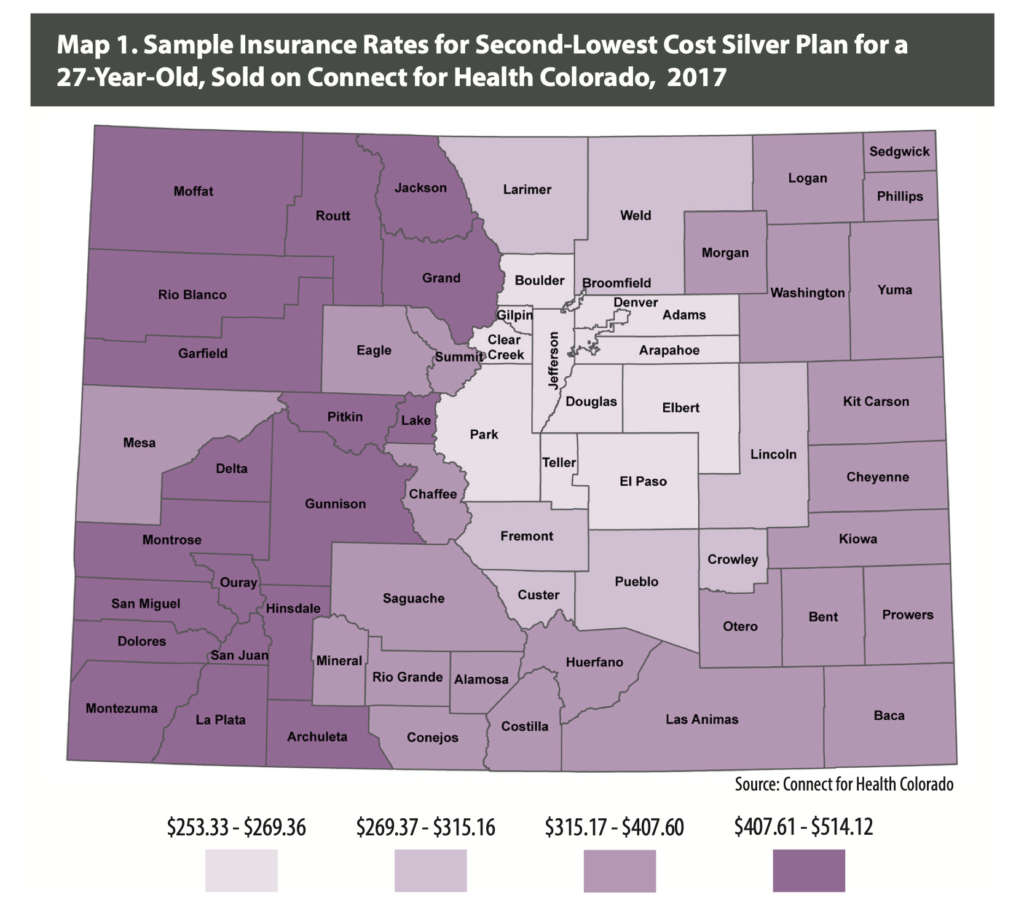

Roberts notes that rural Coloradans currently operate at an incredible disadvantage in the individual insurance marketplace.

“Right now, too many Coloradans are in parts of the state where there’s no choice or competition on the health insurance market,” Roberts said. “And so this will bring choice, bring competition, will make sure that everybody can have access to affordable health insurance coverage.”

A lack of competition in rural Colorado equals high health insurance prices, which Roberts claims puts people between a rock and a hard place.

“When [rural] people go shopping, they either buy the one option that’s there or they don’t get health insurance at all,” said Roberts. “And that one option just keeps going up and up in price.”

Ganahl argues that especially because of the strain of COVID on healthcare, this is the wrong time to introduce a public option.

“Is now the time to strangle those free-market heroes who served us so bravely the past year?” Ganahl asks in her column.

Opponents argue that you don’t have much credibility glorifying the free-market when there’s only one health-insurance company selling insurance in that market, as is the case in parts of Colorado.

But more broadly, while some hospitals may struggle now, so do individuals, argues Fox, pointing for the need for a solution that works for the community.

“Now, more [Coloradans] have lost their health care and many small businesses can no longer afford to provide their employees expensive health insurance,” said Fox. “Coloradans and our small businesses need a long term solution that controls costs and holds the health care industry accountable to provide more affordable health insurance options.”

Ganahl did not respond to a voicemail requesting comment. This post will be updated with any response from her.