Our death rituals for public figures are evolving.

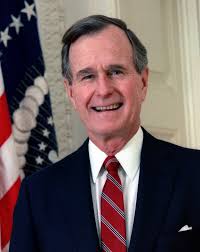

For a moment, obituaries favored the late President George H. W. Bush with the banal pleasantries usually afforded to deceased presidents. Well-wishers from both sides of the aisle hailed Bush’s patriotism, service, decency, and other traits we think we want leaders to have.

Then came the counter-narratives: Bush’s inaction during the AIDS crisis. The generation of war in Iraq he started. His acceleration of the war on drugs and his race-baiting Willie Horton ad. His groping of women. Surely we should have reservations about celebrating such a legacy, many countered.

Now, I’m partial to the latter view — more in that in a moment. But what concerns me more is the third phase in this emerging ritual: the righteous insistence that death is no time to examine a public figure’s life’s work. They’re dead. Be nice.

Or worse: The centrist plea, typified by New York Times columnist Frank Bruni, that “a mix of appreciations and censorious assessments is in order.” Even if you had loved ones die during the AIDS crisis, or a family member die in Iraq, Bruni thinks it’s “possible, even imperative, to acknowledge and celebrate” the late leader’s “valor galore.”

Bruni calls this “nuance.” I call it the opposite.

This being 2018, I get it. Politics feels exhaustingly nasty. Even many lefties crave a conservative foil to the crasser occupants of today’s White House. Folks in the center may just want a break from the yelling.

Team, I feel you. But look a little harder.

Under Bush, the U.S. committed genuine war crimes. In the first Gulf War, our bombers killed 13,000 civilians outright and 70,000 later by deliberately targeting civilian infrastructure. Infants died in hospitals without electricity, while broken sewage systems led to preventable epidemics.

And like the younger Bush’s war, reporter Joshua Holland noted, the elder’s was also premised on lies.

In Bush’s mostly forgotten Panama war, the U.S. reduced a civilian neighborhood to what locals called a “little Hiroshima.” They did it to execute a warrant for drug trafficking, even after the CIA itself collaborated with drug traffickers to fund right-wing death squads elsewhere in Central America.

To cover up the related Iran-Contra scandal, Bush withheld evidence and pardoned six of its architects. Sound like someone you know?

It’s easy to find other arguments elsewhere. Contrary to the “be nice” crowd, I think that’s a good thing.

The terrifying fact is that our national security state is capable of terrifying crimes — no matter who runs the country. It’s unsettling. So there’s a strong temptation to focus on the private virtues of the individual who sits atop it rather than the messy machinery beneath.

And just look what that obscures.

If you don’t hang out with movement progressives, there’s a good chance you never heard anyone say the first Gulf War might’ve been problematic. If you didn’t live through it, you might not have heard of Panama at all, much less the deeper CIA intrigues during the Cold War.

Personally, I believe these acts are crimes that should be atoned for and never repeated. Same goes for mass incarceration, the neglect that led to the AIDS crisis, and other legacies of the era. Taking a rare opportunity to scrutinize them publicly seems more conscientious to me than observing even a well-intentioned silence after their architect’s passing.

We all need a break from arguing sometimes. But new debates, especially on overlooked subjects, bring new vibrancy to our civic life. In death, even flawed politicians can do us that final service.

Peter Certo is the editorial manager of the Institute for Policy Studies and the editor of OtherWords.org.

Correction: this author of this post was initially listed incorrectly as Jason Salzman