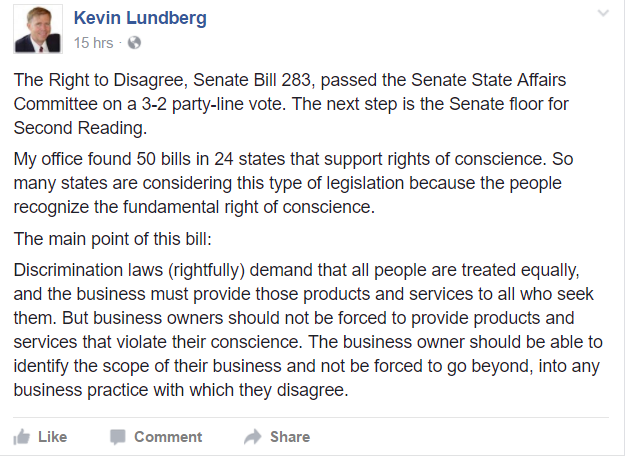

I ran across this post from State Sen. Kevin Lundberg (R-Berthoud). Taking a standard position in the wake of the Hobby Lobby decision, he argues in favor of Senate Bill 283, which would let businesses discriminate on the basis of “the fundamental right of conscience.” That’s shorthand for “religious beliefs.”

I marvel at the dissonance. He writes, “[D]iscrimination laws (rightfully) demand that all people are treated equally” and then contradicts himself in the next sentence: “[B]usiness owners should not be forced to provide products and services that violate their conscience.” He believes your religious beliefs should be a get out of jail free card for violating the anti-discrimination laws that he claims to support.

It reminded me of a couple things. One was Ron Paul’s infamous argument against the 1964 Civil Rights Act:

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 gave the federal government unprecedented power over the hiring, employee relations, and customer service practices of every business in the country. The result was a massive violation of the rights of private property and contract, which are the bedrocks of free society. The federal government has no legitimate authority to infringe on the rights of private property owners to use their property as they please and to form (or not form) contracts with terms mutually agreeable to all parties.

The rights of business owners, according to Paul and Lundberg, should be placed in higher regard than the right of marginalized communities to not be subject to discrimination. This argument is a favorite of conservatives. Perhaps it’s most famous expression was by lawyers for Bob Jones University. They were fighting against the loss of tax-exempt status based on their refusal to admit African American students and their later requirement that they be married to attend. In the seminal 1982 case, they argued that anti-discrimination laws “…cannot constitutionally be applied to schools that engage in racial discrimination on the basis of sincerely held religious beliefs.” The Supreme court disagreed and ruled against them.

I wonder how far Lundberg would take his argument. After all, “right of conscience” can be construed to mean virtually anything. A religious argument against racial intermarriage—that the story of Babel implies races should not mix—was used to defend discrimination against mixed-race couples. In fact, a lower court judge who upheld anti-miscegenation laws prior to the Supreme Court reversal in Loving v. Virginia used this argument explicitly:

Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.

I hope Lundberg will reconsider his argument in light of these facts. Infamous cases in our recent past that have shown it to be flawed. Unfortunately, the poorly thought out and incorrectly rendered Hobby Lobby decision opened the door for future challenges to anti-discrimination laws on these same questionable grounds.