The proposal on last month’s election ballot to restrict abortion in Colorado was expected to be close, but just over an hour after the polls closed on Nov. 3, the race was called. Proposition 115, which would have banned abortion at 22 weeks, lost by 18 percent of the vote.

The election results in Colorado, which has been steadily shifting blue over the last decade, were generally favorable for Democrats. Joe Biden easily defeated President Donald Trump, Republican Senator Cory Gardner was ousted after a single term, and Democrats cinched control of every statewide governing body, a historic victory for the party.

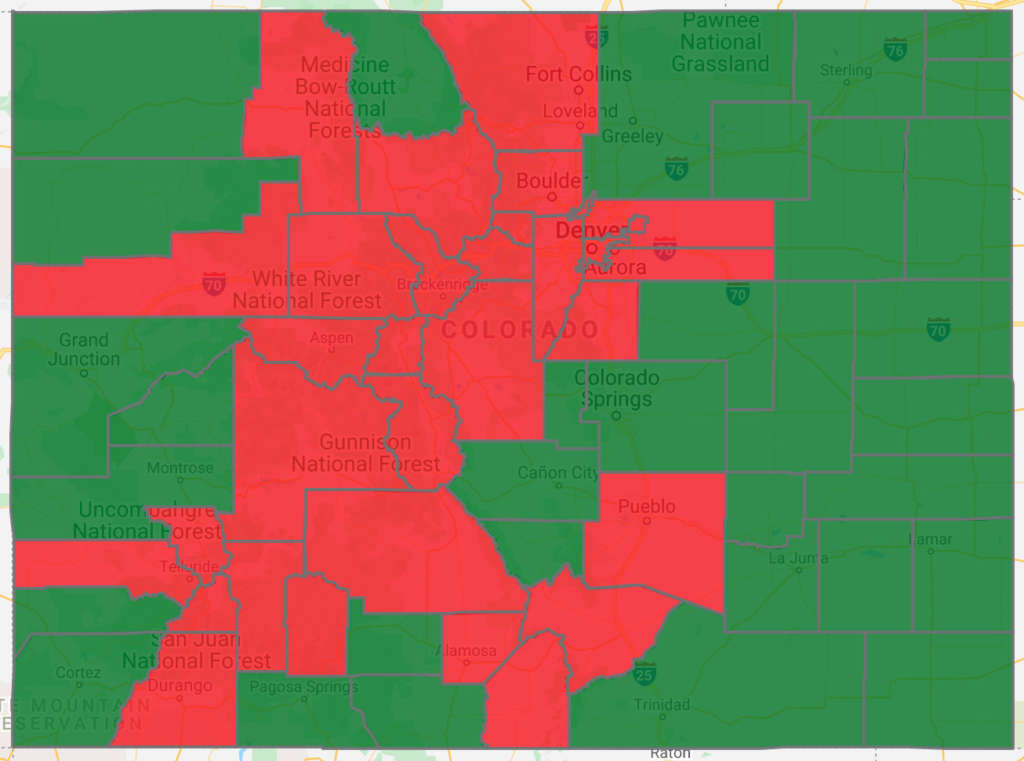

Prop. 115, however, turned out to be one of the most uniting issues on Colorado’s ballot, with more voters rejecting the measure (58.99 percent of voters) than voted to oust Trump (58.1 percent) or Gardner (55.8 percent). In fact, in seven counties where Trump received a majority of votes, Prop. 115 lost, sometimes by a surprisingly wide margin.

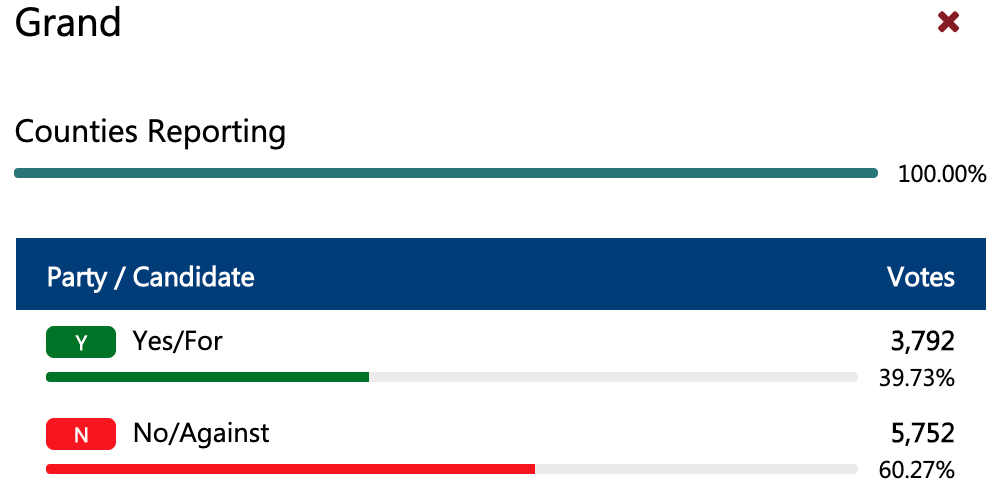

In Grand County, for example, which encompasses rural and mountain communities including Granby, Hot Sulfur Springs, and Winter Park, Trump won with 49.5 percent of the vote over Biden’s 47.7 percent. Just 39.7 percent of Grand County voters, however, voted in favor of banning abortion later in pregnancy.

In deep-red Park County, the rural area to the west of Colorado Springs, Trump won easily, receiving 56.9 percent of the vote. Just 46.9 percent of voters, however, voted for Prop. 115.

It was a similar story in several other counties that went for Trump, many of them mostly rural areas, including Alamosa, Huerfano, Hinsdale, Mineral, and even Douglas County, which has long been considered a stronghold for conservative policymakers.

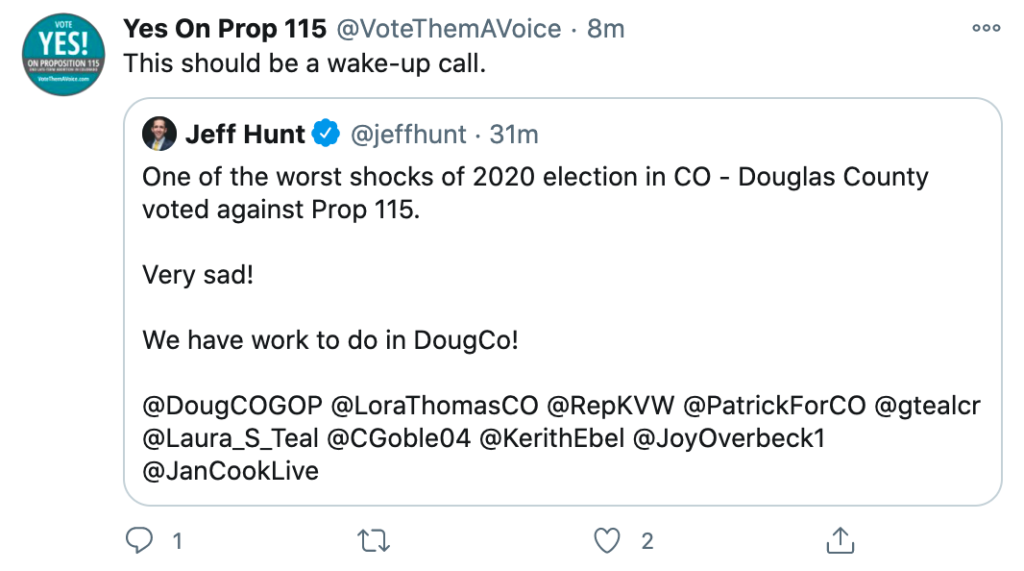

Jeff Hunt, who directs Colorado Christian University’s think tank the Centennial Institute and was a key advocate for Prop. 115, called the Douglas County election results “one of the worst shocks of the 2020 election,” in a Nov. 4 tweet. “We have work to do in DougCo!” Hunt wrote.

Vote Them A Voice, one of the groups behind Prop. 115, retweeted Hunt, adding, “This should be a wake-up call.”

The campaign did not return an email asking it to elaborate. Due Date Too Late, another group behind the initiative, did not return an email requesting comment and asking why it thinks the initiative underperformed compared to Trump in some of the state’s most conservative areas. Backers of the initiative have pointed out, however, that the opposition campaign was well-funded compared to theirs.

“We actually did quite well in Colorado Springs,” said Stefanie Clarke, Communications Director for the No on 115 campaign, noting that the measure received only 52.8 percent of the vote in El Paso County, one of the most socially conservative counties in the state and home to the national anti-abortion organization Focus on the Family. “That’s their turf, that’s their stronghold.”

“They certainly did not come close to the margin they needed there to help offset our lead in other counties,” Clarke said. “And I don’t think they, or anyone else for that matter, necessarily expected that.”

Asked why she thinks the No on 115 campaign performed so well in conservative areas, Clarke said that the campaign’s message that abortion later in pregnancy is a personal medical decision resonated across party lines. She also pointed out that Colorado voters have seen abortion bans on their ballot four times now since 2008.

“Before Prop. 115, Coloradans had rejected abortion bans at the ballot three times in the last 12 years. Voters are tired of being asked to vote on this issue and feel that it has been settled,” Clarke said. “Colorado voters understand that abortion is a personal, private medical decision and should be left to pregnant people, their families, and their health care providers.”

Clarke also emphasized the campaign’s focus on uplifting the voices of those who have had abortions later in pregnancy as central to their winning strategy.

“We felt it was our moral imperative to build an understanding and a sense of empathy around abortion later in pregnancy,” Clarke said. “We were able to destigmatize and humanize those who seek abortion later in pregnancy, what their reasons are, and voters said, ‘You’re right, I’m not going to make that decision for someone else.’ I believe it opened people’s minds in ways they hadn’t thought about this issue before.”

That included TV ads and opinion pieces focusing on the experiences of women with wanted pregnancies who decided to terminate for health reasons and fetal diagnoses.

“This margin of victory shows that it’s critical to build those voices into the narrative,” Clarke added.

The fact that Trump has repeatedly attacked later abortion care since his first campaign for president gives these results added significance.

Trump’s unrelenting promotion of misinformation about abortion later in pregnancy, which he talks about in graphic terms and falsely claims happens on the final day of pregnancy, has been a rallying cry for abortion foes over the past few years.

That, in combination with his advancement of anti-abortion policies like the global gag rule, his attacks on Planned Parenthood, and his nomination of Supreme Court justices that he believes will overturn Roe v. Wade, have caused some of the country’s most powerful anti-abortion activists to laud him as the “most pro-life president” in history.

Understandably, proponents of Prop. 115 appeared to take Trump voters for granted, focusing their efforts instead on winning over Democrats and unaffiliated voters by framing the measure as nonpartisan and promoting the narrative that the Democratic Party is too extreme on abortion.

Democrats for Life of America, an organization that exists to promote that exact narrative and elect anti-abortion Democrats nationwide, was one of the initiative’s biggest backers.

One TV ad, for example, featured Terrisa Bukovinac of Democrats for Life, who has received national attention as a self-described pro-life feminist, atheist, and vegan.

“Democrats must be pro-life if we are to hold true to our Democratic values of equality, non-violence, and non-discrimination,” Bukovinac says in the ad. “It’s ok for Democrats to vote yes on 115.”

Dr. Thomas Perille, a retired internist from Englewood and President of Democrats for Life of Colorado, was one of the initiative’s most vocal advocates. He did not return an email requesting comment and seeking to know if he still felt that anti-abortion policies were palatable to Democratic voters in the state following Prop. 115’s failure.

Is the GOP Platform on Abortion Too Extreme for the Party’s Electorate?

We’ve heard the argument time and again that the Democratic Party shouldn’t have an abortion litmus test for candidates if it wants to win in more conservative areas, occasionally from party leaders themselves. The theory was particularly popular following Trump’s election as the party underwent a period of soul-searching.

Colorado’s election results challenge this notion and support an alternate theory: that the Republican Party platform on abortion is too extreme for their own electorate, and that even Trump voters aren’t necessarily persuaded by the president’s diatribes on abortion later in pregnancy.

There are indications of this at the national level, as well. While Democrats for Life remains an active political organization, its electoral success has been steadily dwindling. The organization endorsed just two anti-abortion Democratic congressional candidates in the 2020 general election, both of whom were unsuccessful. One of them, U.S Rep. Collin Peterson of Minnesota, had been serving in Congress for nearly three decades. U.S. Rep Dan Lipinski of Illinois, another anti-abortion Democrat, lost in a 2020 primary race against an opponent who favors abortion rights.

At least one Republican who deviates from their party’s platform on abortion fared better in 2020; Sen. Susan Collins of Maine, who tends to side with Democrats on the issue, held on to her seat in a hotly contested race.

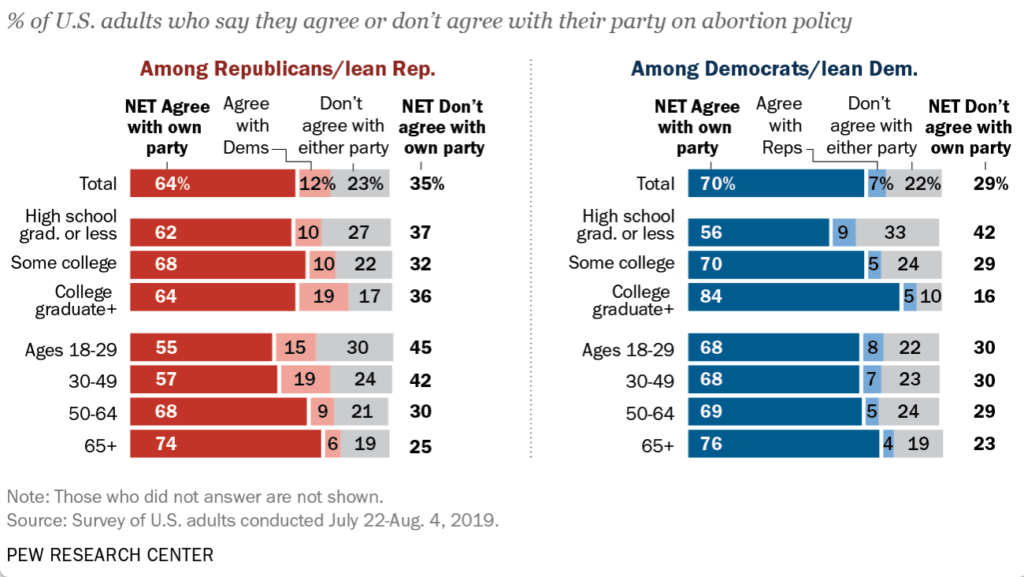

What’s more, polling from the Pew Research Center indicates that Republicans are more likely than Democrats to disagree with their party on abortion. Only 55 percent of Republicans between the ages of 18 and 29, in particular, agreed with their party, compared with 68 percent of young Democrats, according to the poll.

It’s rare that voters get a say on whether to ban abortion later in pregnancy; the vast majority of the 43 states with gestational bans on abortion enacted these policies through state legislative action, not ballot initiatives. The results from Colorado’s election therefore provide rare data on how voters view abortion later in pregnancy. For supporters of abortion rights, that data is promising.