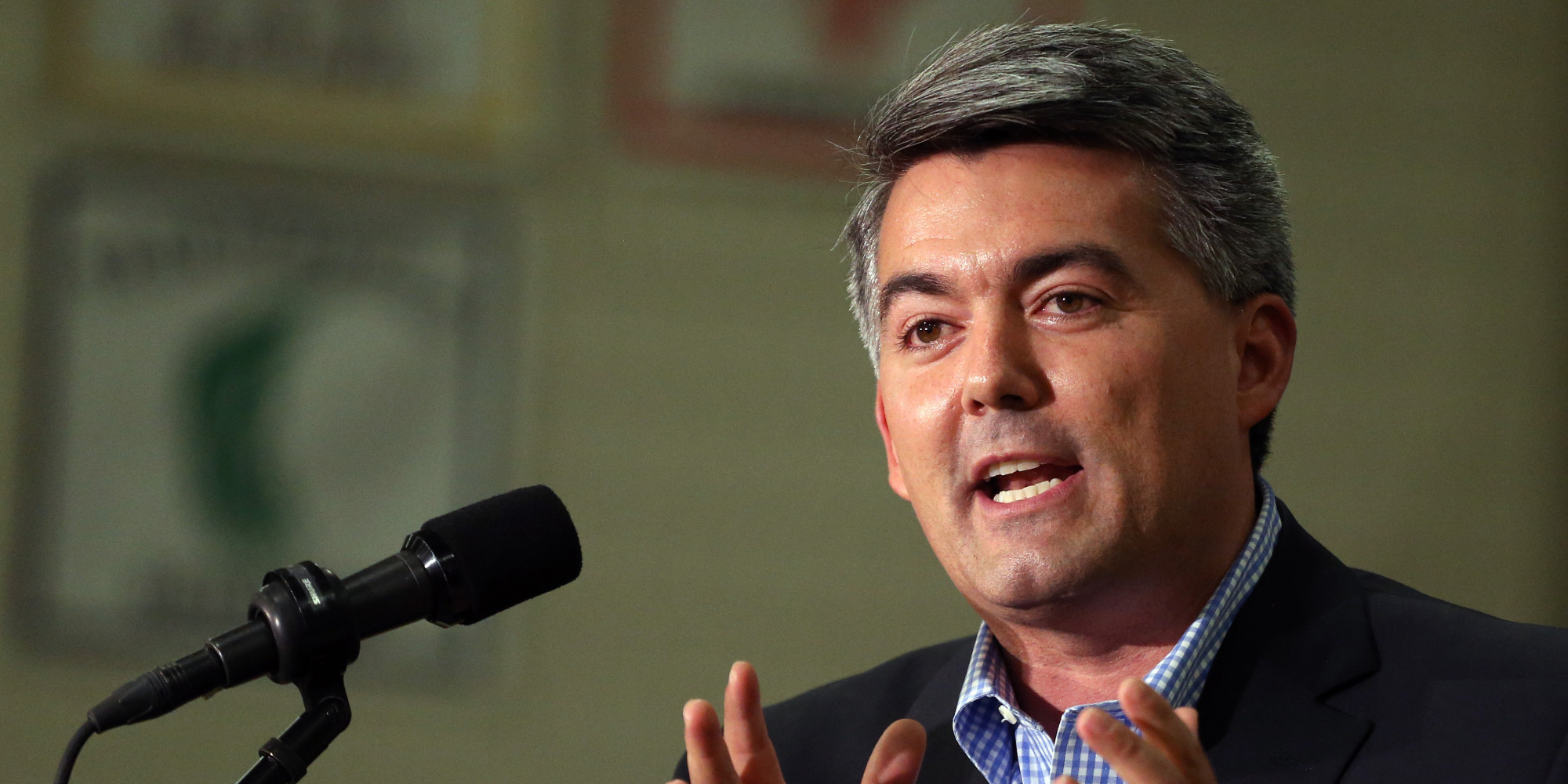

In his short explanation of why he voted with Trump for a national emergency to build a border wall, Colorado Sen. Cory Gardner did not explain why he told at least two Colorado media outlets that he opposed the national emergency.

The two statements are unequivocal, starting with his March 13 statement to KOA radio’s Marty Lenz, one minute into the interview:

“I think declaring a national emergency is not the right idea,” said Gardner on air. “I think Congress needs to do it’s job. There may be some dollars that are available for reprogramming. I’m not sure what they would be, and that would be a matter of a lot of debate because Congress holds the purse strings.”

The next day, Colorado Public Radio’s Ryan Warner Thursday got a similar response from Gardner.

Warner: How do you get the message to him that you don’t want him to perhaps declare a national emergency, as has been hinted? Or, raid other funds for this. How does —

Gardner: Well, it’s pretty simple. I’d tell him that in person, that I think Congress needs to do its job.

Warner: Have you done, that? And do you —

Gardner: I have.

Gardner’s office did not return a call seeking to know why he previously held such a firm view on the national-emergency issue–and what made him do an about face on it.

After the interviews, Gardner issued a statement saying he was still undecided on the national emergency.

“I’m currently reviewing the authorities the Administration is using to declare a national emergency,” stated Gardner.

But he did not explain what he was thinking before and why.

His statement on Wednesday hints that he now believe there is in fact a national emergency on the southern border, and so maybe this affected his thinking:

“Between October and February, border patrol apprehensions were up nearly 100 percent and since 2012, border patrol methamphetamine seizures are up 280 percent,” Gardner said in his statement.

The New York Times has pointed out that it’s apprehensions of families that have increased over time, pointing to a humanitarian crisis. Overall apprehensions are down historically, and ports of entry, not the wider border, is the gateway for most drugs entering America from Mexico.