Campaign signs are packed in tight clusters on the roadside as Highway 24 emerges from the mountain pass and levels-out into Woodland Park. It’s a familiar scene by now in the small town which has spent the past three years fighting for its own future. The conflict has well-defined lines by this point, and the campaign signs – which have sprung like Columbines from the snow over the past month as the town’s April 2nd municipal election draws near – are clustered to reflect them.

The conflict, as anyone who has paid attention to Woodland Park in recent years knows by now, is not between Republicans and Democrats, or between believers and non-believers. Rather, it is between a large contingent of Woodland Park residents, and the members of a controversial ministry whose leader has openly stated his desire to conquer the town.

Over the past decade, Andrew Wommack Ministries and the affiliated Charis Bible College have dramatically expanded their footprint in Woodland Park, and that expansion came with some growing pains: traffic at the turnoff to the ministry’s massive headquarters, local squabbling about property taxes, and concerns about whether the town’s water supply could withstand the ministry’s expansion all emerged as small flashpoints in the early years after Wommack’s organizations moved to town. The conflict currently raging between the ministry and the townspeople, though, did not spark to life until April 2021, when Andrew Wommack made his intentions clear.

“Man, as many people as we have in this school here, we ought to take over Woodland Park,” he said from the stage at an event held by his political organization, Truth & Liberty. “This county ought to be totally dominated by believers,” he said. “We have enough people here in this school we could elect anybody we want.”

The comments drove a wedge between the ministry and the town it calls home, and residents on both sides of that wedge have spent the subsequent years attempting to navigate what the declaration means for their community. Wommack followers feel like the townspeople are persecuting them for their faith; other locals say they would have been happy to coexist, but will not stand for being taken over.

Wommack’s quip that April day was not idle chatter: within months of those comments, Wommack and his organizations – which occupy hundreds of acres just outside the town center, constantly patrolled by private armed security – were supporting a controversial slate of school board candidates to take control of the Woodland Park School District (WPSD) and turn that secular, nonpartisan institution into one with a decidedly conservative and Christian bent. As I have covered at length, the board’s takeover triggered two years of turmoil, involving public spats, a wrongful arrest, and a controversial social studies program which the new school board became the first governing body in the nation to approve.

Now, a fight which has consumed the school board since 2021 is coming for the city council, and the local stakes are even higher than they were during the school board fight. Controlling the school board was an ideological victory for Wommack. As one of the town’s major landholders and business interests, controlling the city council could have significantly more practical impacts for the man and his ministry empire.

It is likely not a coincidence, then, that four candidates aligned with the ministry are currently running for city council. Nor is it likely a coincidence, given the negative sentiment among townspeople about Wommack’s takeover, that those candidates have attempted to keep their ties to the ministry under wraps.

When Wommack’s slate won the school board in 2021, they did so with only one of Andrew Wommack’s actual acolytes on the ballot – Sue Patterson, who still serves on the WPSD board – and three other candidates who were ideologically compatible with the ministry, but not personally tied to it prior to their runs for office. The de facto council slate is different: three of the four Wommack-aligned candidates running for office in Woodland Park this year have been students or employees at Andrew Wommack’s organizations, and the fourth has close ties to members of those organizations. If all four win seats on council, they will hold a majority, and, in the eyes of concerned locals, Andrew Wommack will have made good on his threat.

He will have taken over Woodland Park.

Woodland Park’s city council has seven members: the mayor and six councilors. Instead of being drawn into districts, the mayor and all six councilmembers are elected at-large by votes of the entire town. This year, the mayoralty and four of the six council seats are up, and every voter in town will have the opportunity to vote for four of the eight candidates on the ballot. The four candidates who receive the most votes win. Only one incumbent member of council, Frank Connors, is seeking reelection.

As with so much in small town America, the drumbeat of concern about the current crop of candidates started in the local Facebook groups. As city council contenders began declaring their candidacies over the past few months, locals noticed something interesting about a few of them, and they started posting about it online. Four of the candidates, posters alleged, were tied to Wommack – and, more alarming to them, those candidates appeared to be hiding those ties from voters.

When I first stumbled across this chatter several weeks ago, I took it with a grain of salt: the anti-takeover organizers in Woodland Park are sharp and savvy – and they have also spent the past few years having their nerves frayed beyond recognition. It’s not surprising, I told myself, that they may have gotten a little jumpy. What are the chances, I asked myself, that there is a secret pro-Wommack slate running for city council? Sure, Wommack promised to takeover the town, boasting about being able to elect anyone his people wanted, but this? This sounded like something out of a bad novel.

Then I looked at the evidence, and I discovered, not for the first time, that the local organizers in Woodland Park were correct: at least three of the four suspected Wommack-aligned candidates do, in fact, have ties to Wommack – and all of them seem interested in concealing those ties.

The four are Don Dezellem, Eric Lockman, Tim Northrup, and current council incumbent Frank Connors.

Of the four, Dezellem’s ties to Wommack are the least direct. According to his official candidate bio on the city website, Dezellem has spent his career working in retail management for major corporations, including 7-Eleven and Walmart. When Dezellem previously sought a council seat in 2022, he was dogged by allegations of connections to Wommack and Charis Bible College, and put out a statement denying those connections.

“This statement is concerning my involvement with Charis Bible College and Andrew Wommack,” the 2022 statement read. “I have no involvement with them. I have never been a student at Charis or have taken donations from Charis or Andrew Wommack.”

Dezellem does have close ties, however, to Charis graduate and current councilman Robert Zuluaga, with whom he has promoted a series of “Patriot Academy” classes. Patriot Academy is a far-right training organization, founded by a man named Rick Green, which promises to “train citizens to understand and influence government policy with a Biblical worldview.” In both 2022 and 2023, per social media posts, Dezellem and Zuluaga promoted a series of “Biblical Citizenship” classes based on Green’s teachings and Patriot Academy’s programming.

While Dezellem – who did not respond to my inquiries regarding this article – might not have a direct relationship with Wommack’s organizations, Rick Green and Patriot Academy do. Green has appeared on Wommack’s Truth & Liberty show several times, and hosts the daily Truth & Liberty-affiliated radio program “WallBuilders Live!” with Wommack-aligned historian David Barton.

Though Don Dezellem’s ties to Wommack run through a series of intermediaries, the other three Wommack-affiliated candidates can be connected back to the ministry much more directly.

For Eric Lockman, the connection is as direct as it can be: Lockman and his wife both studied under Wommack at Charis Bible College. In a video the two produced in January 2023 – promoting their farm-slash-ministry – Lockman and his wife were candid about the fact that Charis is what brought them to Woodland Park, in the first place. If it were not for Andrew Wommack, the Lockmans would not be in Woodland Park, and Eric Lockman would not be running for city council.

Despite Lockman’s prior openness about how he ended up in Woodland Park, the official bio he submitted to accompany his candidacy makes no mention of it. In the biography, Lockman notes that he currently serves as the Director of Operations at his local church, but does not name the church.

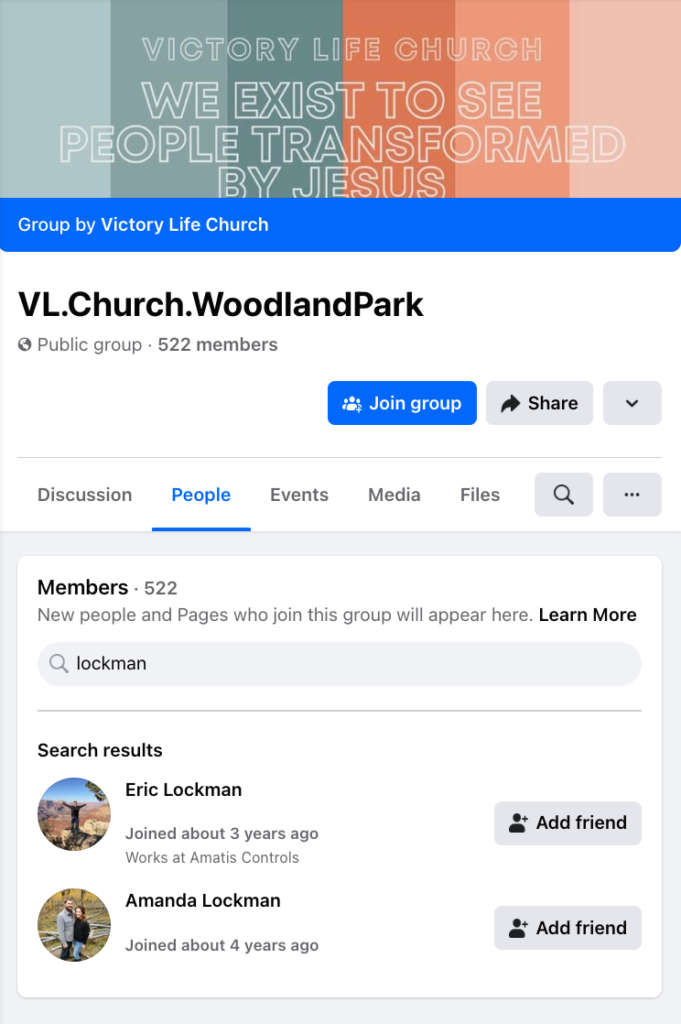

The church, I have learned, is Victory Life Church of Woodland Park, which meets at the headquarters of Andrew Wommack Ministries. Both Lockman and his wife are in the church’s Facebook group.

Lockman did not reply when I reached out to him for this piece.

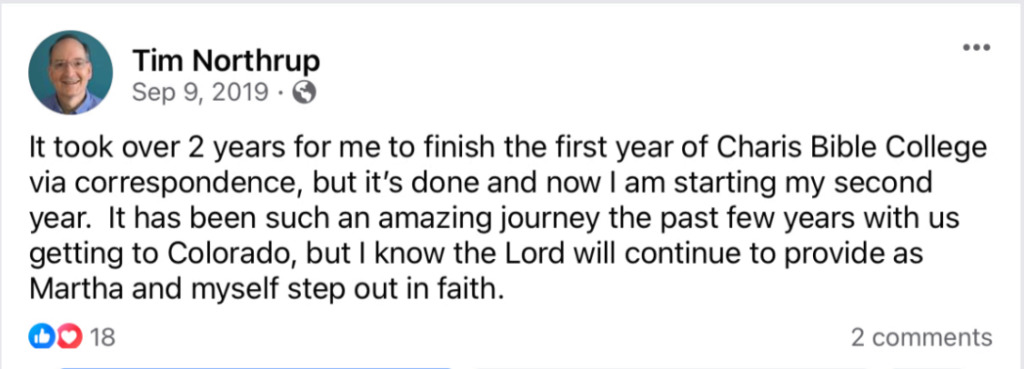

Of all the candidates currently running for city council in Woodland Park, Tim Northrup’s connection to Andrew Wommack is arguably the closest: he works for the man.

According to his LinkedIn profile, Northrup has been employed as a phone minister in the Andrew Wommack Ministries call center since 2019. When Northrup submitted his official biography to the city to accompany his candidacy, he did not deem these five years of service relevant: the bio makes no mention of any personal or professional connection to the ministry at the center of so many local discussions. Instead, Northrup’s official bio centers the earlier part of his career, spent working as an IT manager in the banking sector.

Despite omitting the information about his Wommack ties from the information he distributes to voters, Northrup’s social media history shows years of open support for Andrew Wommack Ministries and Charis Bible College. Northrup’s social media history also shows that, in addition to working for Wommack’s call center, he also studied at Charis. Northrup did not respond to my outreach about this article.

Frank Connors, the lone council incumbent seeking reelection, is also tied to Wommack and his organizations. Though Connors himself does not appear to have ever been a student at Charis, his wife, Jennifer, studied at the school, and the couple appears to maintain a close relationship with the Wommack community.

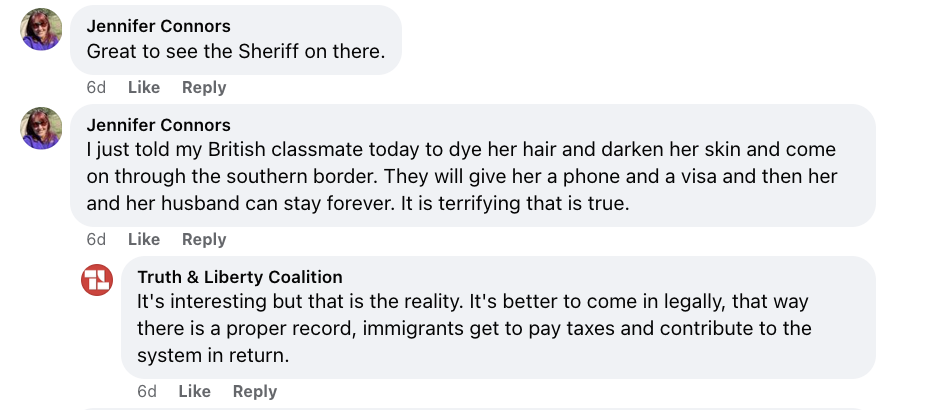

Frank Connors has liked and promoted content from Charis Bible College and Truth & Liberty on Facebook, and Jennifer Connors can regularly be found interacting in the comments section of Truth & Liberty videos.

In the comments beneath one of those videos – the March 13th, 2024 Truth & Liberty Live Call-In Show, in which Wommack interviewed Teller County Sheriff Jason Mikesell – Jennifer Connors left a racially tinged comment about immigration, and the official Truth & Liberty account chimed-in to agree with her.

“I just told my British classmate today to dye her hair and darken her skin and come on through the southern border,” Connors wrote. “They will give her a phone and a visa and then her and her husband can stay forever. It is terrifying that is true.”

“It’s interesting but that is the reality,” Truth & Liberty replied. “It’s better to come in legally, that way there is a proper record, immigrants get to pay taxes and contribute to the system in return.”

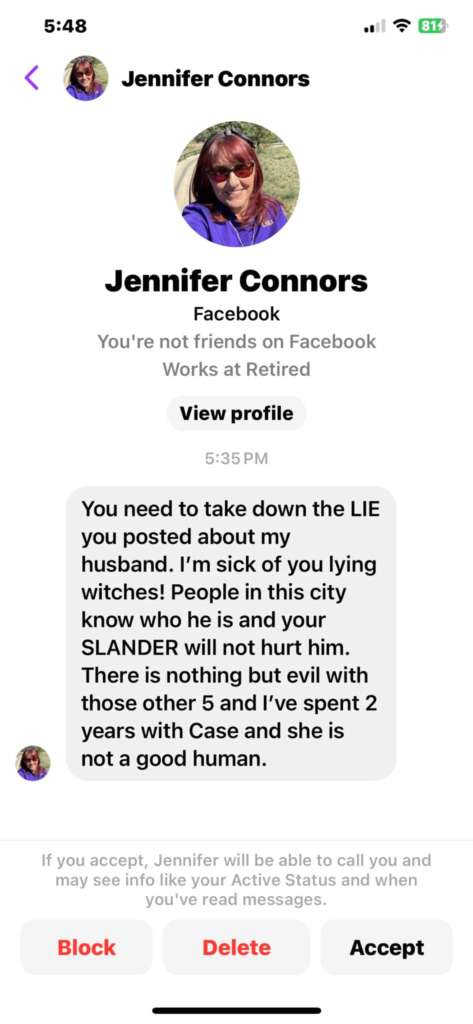

When Bridget Curran, an active member of the anti-takeover contingent, posted about Connors’ connections to Charis and Wommack, Jennifer Connors sent her an angry Facebook message. “You need to take down the LIE you posted about my husband. I’m sick of you lying witches!” the message started, before continuing apace.

As with the other three Wommack-connected candidates, Connors’ official bio makes no mention of his connections to the controversial ministry. Also like the other three, Connors did not reply to my request for comment on this story.

Like others, Curran wonders how a ministry can engage in political activity like this.

“What I find alarming is that Wommack claims tax-exempt status due to being a religious organization,” she told me, “Yet he holds candidate academies, sends out political mailers, and promotes their candidates via his Truth & Liberty broadcast.”

“I’m not sure how he gets away with all this,” she said.

It’s a question of increasing importance as American churches of all kinds become more political. It is also a question the people at Wommack’s organization seem to have considered, and appear to have found a way around.

Crucially, Wommack’s 501(c)(3) ministry organizations do not appear to be providing any material support to the candidates in any way which would violate either their nonprofit obligations under the Johnson Amendment, which prohibits (c)(3)s from engaging in political activity. Wommack’s 501(c)(4) political arm, Truth & Liberty, is not bound by the same obligations, though. Unlike Charis Bible College or Andrew Wommack Ministries, Truth & Liberty would be well within its rights to engage in political spending to support the candidates, but is prohibited from directly coordinating with them.

The separation between the ministry organizations and the political organization is not as clear-cut as it might sound, though. According to Truth & Liberty’s most recent tax filing, Truth & Liberty staff “are compensated by a related organization, Andrew Wommack Ministries, Inc.” The tax filing also notes that Truth & Liberty “shared employees with Andrew Wommack Ministries, Inc.” The arrangement – with 501(c)(3) ministry funds paying the salaries of 501(c)(4) political staffers – raises eyebrows, but there is no public indication that the IRS has noted or objected to it. With a sizable portion of nonprofit regulations hingeing on what percentages of the budget are dedicated to what activities, it is possible that the arrangement is completely up to snuff.

Truth & Liberty did not reply to my inquiries regarding this story.

According to a 2022 Pew poll, a large majority of Americans want to see the Johnson Amendment enforced, and see ministries kept out of the political realm. It’s a position held by religious and non-religious Americans alike.

Tax status, however, is not why the people of Woodland Park are concerned about the political activities of the man who promised to take over their town. They are concerned because he promised to take over their town. They are concerned because, since that promise was made, the tension between the ministry and the other locals has impacted life in their small corner of the world. They are concerned because, in the three years since Andrew Wommack dreamed of taking over Woodland Park, he has taken steps to make that dream a reality.

“I am flabbergasted at the amount of influence Wommack already has over our once tight-knit community,” Bridget Curran told me, reiterating that Wommack’s organizations have already “been able to take seats on our local school board and city council.”

Now, staring down the possibility of a Wommack-aligned city council majority, locals are wondering what the future looks like with the ministry in control, and wondering if the ministry’s vision for the future of the town has room for them in it. After all, Wommack did not say “we ought to peacefully coexist with Woodland Park.” He said “we ought to take over Woodland Park.” Wommack did not say “we ought to have more Christians in local office.” He said “this county ought to be totally dominated by believers.”

What Andrew Wommack proposed was not coexistence, it was domination. With a slate of Wommack-aligned candidates now running for city council, some locals are left wondering if domination is just around the corner.

“The implications, if the new city council majority is [made up of] Wommack supporters, could prove detrimental to other locals,” Curran, a 4th-generation resident of the area, said. Like many others, Curran worries that a Wommack-aligned council majority would continue granting the ministry property tax exemptions for their planned expansions, placing increasing strain on local services. “There are water, road, and emergency service issues already. We can’t rely on sales tax alone to bear the burden of ensuring those services are maintained and sufficient for our area.”

The practical implications could be enormous for the future of development in Woodland Park. In the minds of most locals I have spoken to, though, the weight of those practical implications still falls behind the social implications. For Bridget Curran, it’s about family and the future. Curran – who bears no ill will towards Charis students or members of Wommack’s community, but resents the takeover attempt and wonders about the future – is currently raising the 5th generation of her family on the soil of Teller County. It’s her home, and she wants it to stay that way. She does not have a wish list of policy ideas she wants the next city council to take action on; she just wants to know who they work for.

“I just want a city council which can remain neutral and do what’s best for Woodland Park, not just what’s best for Andrew Wommack.”