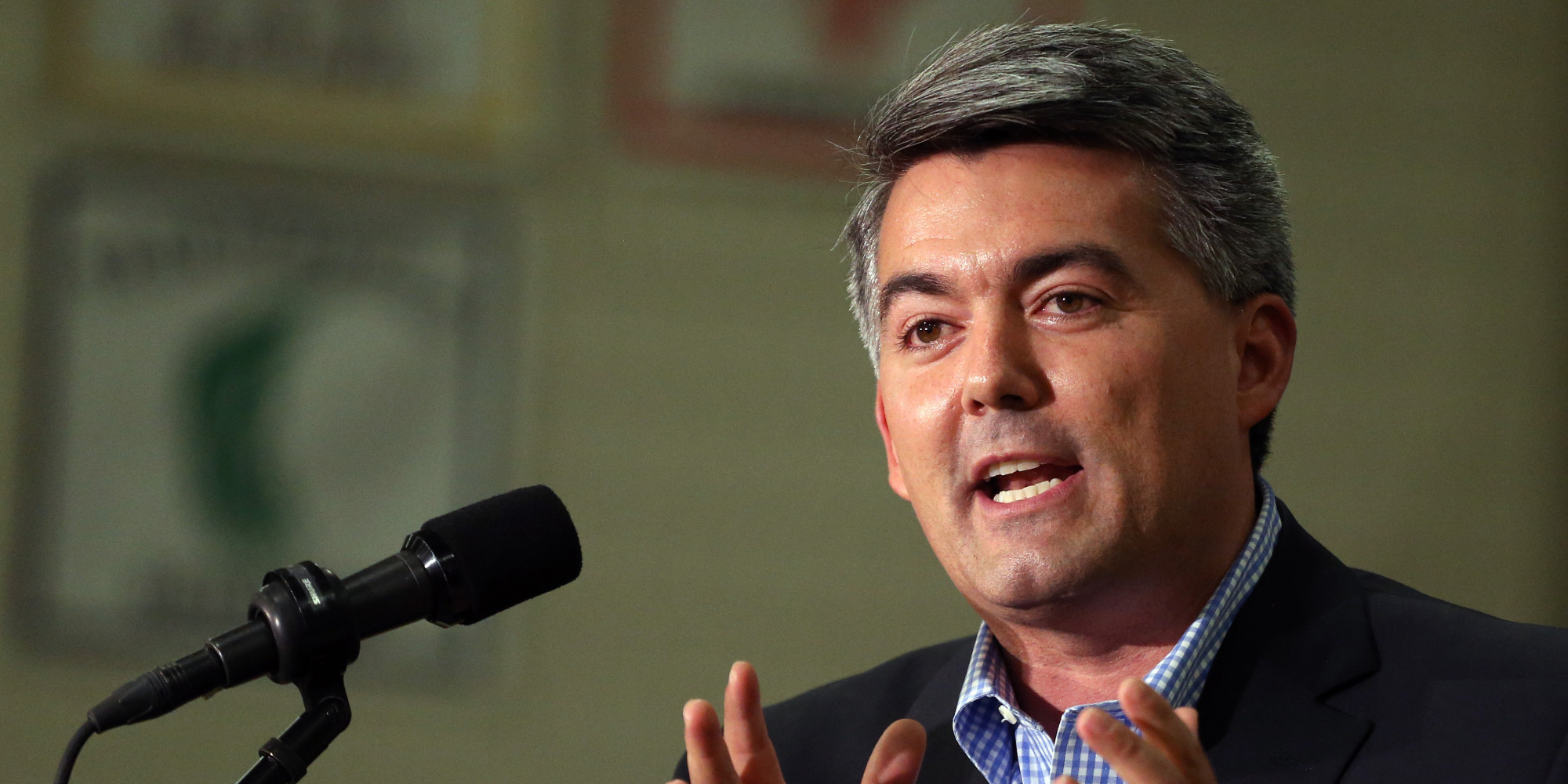

At the end of the election, U.S. Sen. Cory Gardner jetted around rural Colorado with Walker Stapleton, who was the flailing Republican nominee for governor.

Gardner, who didn’t make any Front-Range stops, appeared to be aware of what was coming, with the rural-urban divide both in Colorado and nationally, when he pleaded with Republicans in Grand Junction to vote to stop “some kind of liberal policy agenda that’s going to be run through the Front Range only.”

“This is an opportunity for Grand Junction, for Mesa County, from corner to corner in this state, including the part of the state where I live way out on the Eastern Plains, that every job matters in this state, that every idea can be put to good use in this state, and not just some kind of liberal policy or agenda that’s going to be run through the Front Range only,” Gardner told the Grand Junction Sentinel.

When the election hit, it was clear, at least in Colorado (but not in a state like Missouri), that the rural red voters had no hope of withstanding the blue wave from metro area.

Gardner stayed away from the Front Range during his tour with Stapleton, presumably in hopes of not making it worse.

Some Republicans have been arguing that Stapleton was a weak candidate and Gardner can do better.

Failed Congressional candidate Mike Coffman of Aurora would likely laugh at this, as he did last week, and say, with Trump in the mix and expected to remain stuck in the mix in 2020, it doesn’t matter.

Gardner actually got fewer votes in 2014 (983,891) than Stapleton did this year (1,076,916), which is a little-discussed data point that doesn’t bode well for Gardner.

Neither does the fact that the setbacks measure, Amendment 112, got more votes (1,113,143) than Stapleton.

It’s true that lots more people voted in this mid-term than 2014–and bottom line, Gardner beat Democrat Mark Udall.

But the GOP base seems to hate Gardner, so the chances of him bringing home a red wave of voter like he tried to do in Grand Junction in early November, to compete with unaffiliated and Democratic voters, are low–and the numbers aren’t there anyway.

As a matter of fact, everywhere you look, nationally and locally, the election results and political dynamics paint a bleak picture for Gardner. Where does he get the votes to win in Colorado?