A decision by the History Colorado museum to remove references to former Denver Mayor Benjamin F. Stapleton in its Ku Klux Klan exhibit, even though he’s one of the most prominent Klansmen in Colorado history, has led Republican gubernatorial candidate Steve Barlock to accuse fellow GOP candidate Walker Stapleton of directing his family’s foundation to donate to the museum to cover up the Stapletons’ white supremacist roots.

The display, which describes the history of the KKK’s political influence in Colorado, currently does not mention Denver’s former mayor, but he was referenced multiple times in History Colorado’s display on the Klan before the exhibit was replaced and altered in 2012, when the museum moved to a new building, according to archival photos provided by the museum to the Colorado Times Recorder.

Mayor Stapleton, who was Colorado Treasurer Walker Stapleton’s great-grandfather, was a high-ranking member of the KKK. He served as Denver Mayor from 1923 to 1931, during which time the white supremacist group exercised political influence throughout the state, and in Denver in particular, by electing a handful of members and allies into government offices.

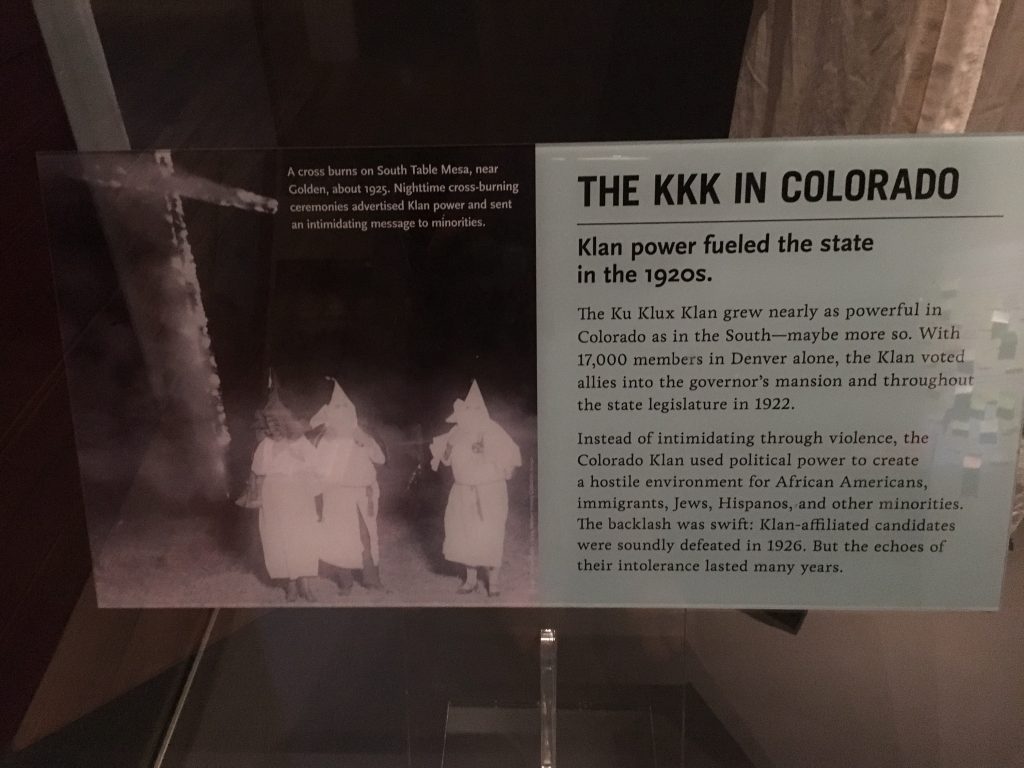

The new display, which sits within the “Colorado Stories” exhibit, references the Klan’s “17,000 members in Denver alone,” and how they “voted allies into the governor’s mansion and throughout the state legislature,” but fails to mention the mayor.

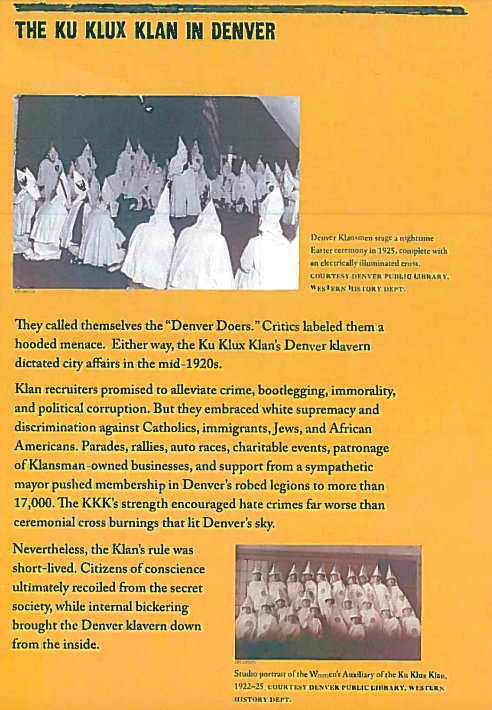

In contrast, the old display, which featured many of the same artifacts, had text panels that made multiple mentions of the mayor’s office.

As the old version of the display explains, “Parades, rallies, auto races, charitable events, patronage of Klansman-owned businesses, and support from a sympathetic mayor pushed membership in Denver’s robed legions to more than 17,000.”

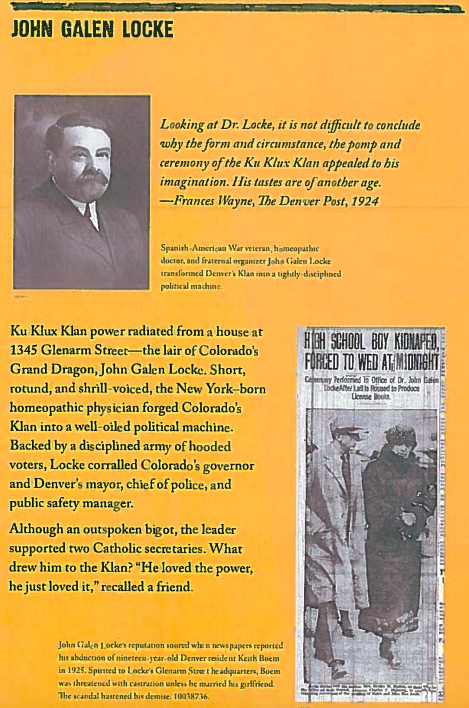

It goes on to mention Stapleton’s relationship to Colorado’s Grand Dragon John Galen Locke, stating, “Backed by a disciplined army of hooded voters, Locke corralled Colorado’s governor and Denver’s mayor, chief of police, and public safety manager.”

Barlock doesn’t believe the current absence of references to Mayor Stapleton in the museum’s KKK exhibit to be an accident, but rather a revisionist version of history preferred by Walker Stapleton, whose family’s foundation has donated more than $50,000 to the museum since 2012, when the new museum opened and the changes to the display were made.

Public tax records from the Stapleton family’s foundation, called the Harmes C. Fishback Foundation Trust, show that yearly donations quadrupled once History Colorado moved to the new museum building and the new KKK display was put in place.

Contributions in the amount of $12,500 were made yearly to History Colorado, which is also known as the Colorado Historical Society, from 2012 to 2015, with a donation of $5,000 in 2016. Prior to 2012, the foundation made smaller yearly donations to History Colorado, usually in the amount of $3,000, according to records dating back to 2001.

The Harmes C. Fishback Foundation Trust has long been run by the Stapleton family. Walker Stapleton’s wife, Jenna Stapleton, is the current executive director.

Annual reports from History Colorado also show yearly donations of up to $999 from Benjamin F. Stapleton, III, another descendant of Mayor Stapleton who’s also a trustee of the foundation.

In Barlock’s opinion, Stapleton doesn’t have any right to try to distance himself from his family’s past, especially considering that Republicans are “all about family,” he said.

“Admit that they’re your family, admit their wrongs, but admit it to the public and don’t try hiding it and definitely don’t try donating your way out of it if you’re so rich,” said Barlock. “I mean, that’s just what they do. When you have that much power and money, you can obviously try to erase history. Unfortunately there are people in your family’s history that they’ve affected, my family being one of them.”

“I don’t think donating money to the Colorado History Museum so there are no names on the display of the KKK is appropriate,” Barlock said.

For Barlock, disdain for the Stapleton family is something of a family heirloom that dates back to the zenith of the Klan’s influence in Denver. Barlock remembers his father relaying a story to him about how the Klan would hold cross-burning ceremonies right across the street from his grandfather’s house in Golden.

So when Barlock used to visit the old Colorado History Museum during his youth, he said he would take particular notice of details surrounding Mayor Stapleton.

“Growing up as a child, probably from Christ the King [Roman Catholic School] or Hill [Middle School] or even at Manual High School, we went to the old history museum, so it’s something we looked at, and we’d see Stapleton and the names of those people,” said Barlock. “I probably have a paper that I did on it. It’s part of family history.”

It’s not surprising, then, that when Barlock first visited the new museum on Colorado Day of last year, which marks the August 1 anniversary of the state, he took particular notice of changes that had been made to the display dealing with the KKK’s influence in Colorado.

He noted that the display was less prominent than it had been in the past, describing it as “tucked away.” And he also noted the absence of references to Mayor Stapleton.

“That’s not very historically correct,” said Barlock, who says he then walked to the lobby of the building and saw the Stapletons’ foundation on a wall listing the museum’s donors.

History Colorado said in an email to the Colorado Times Recorder that Mayor Stapleton’s absence from the exhibit was unintentional.

“The decision was made by exhibit developers and editors to maintain a wider narrative to focus on Colorado, rather than limit to Denver. In addition, our text panels are often limited to under 100 words,” said Communications Manager Brooke Gladstone. “There was no intentional decision to eradicate or avoid mention of Mayor Stapleton, rather to focus on the wider lens of the Klan in Colorado.”

The past version of the text panel obtained by the Colorado Times Recorder is indeed lengthier and more detailed than the one that exists at the museum today.

But the current text panel actually does focus on Denver, mentioning the proliferation of the Klan in Denver and the group’s political allies in the very same sentence, reading, “With more than 17,000 members in Denver alone, the Klan voted allies into the governor’s mansion and throughout the state legislature in 1922.”

Another Denver-specific detail is found in the photo used on the text panel, which shows a Klan cross-burning ceremony at South Table Mesa near Golden around 1925.

Mayor Stapleton actually attended one of those ceremonies South Table Mesa, during a recall election that the Klan helped him win, right around the time that photo was taken.

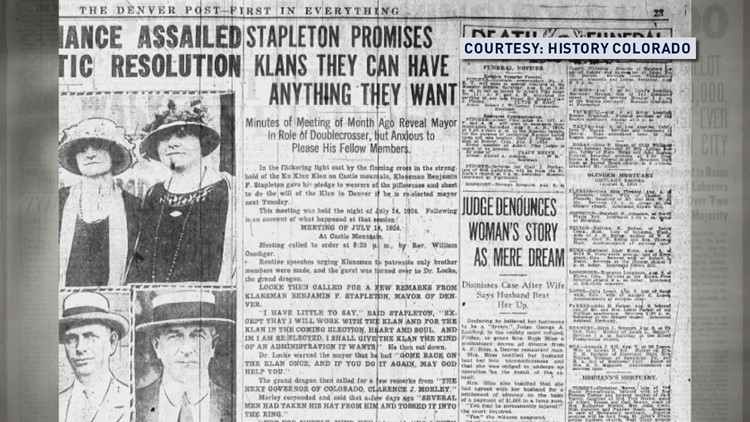

According to Robert Goldberg, author of Hooded Empire: The KKK in Colorado, Stapleton told Klan members at a gathering on July 14, 1924, “I have little to say, except that I will work with the Klan and for the Klan in the coming election, heart and soul. And if I am re-elected, I shall give the Klan the kind of administration it wants.”

With Klan support, Stapleton won his recall election by a landslide, and the KKK burned crosses to signify their victory.

Neither the Stapleton campaign nor his family’s foundation responded to multiple requests for comment. Stapleton is widely considered the frontrunner in the GOP gubernatorial primary.

History Colorado’s omission of the former mayor’s political influence doesn’t stem from a lack of historical artifacts showing Benjamin Stapleton to be a leading figure in the Klan’s history in Colorado.

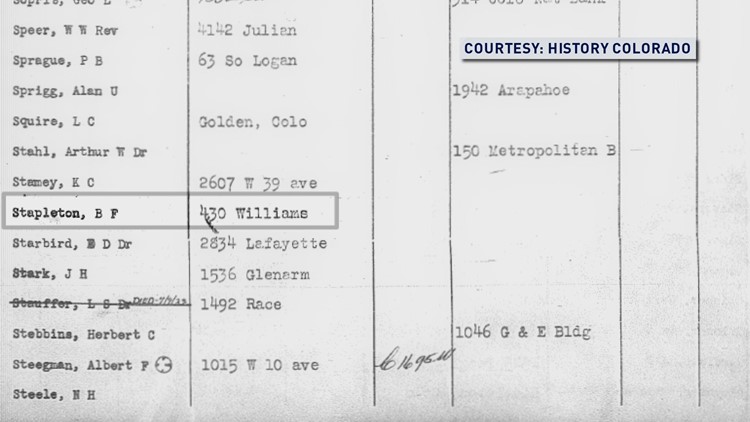

Artifacts provided by the museum that show Mayor Stapleton’s allegiance to the KKK recently appeared in a 9News story by Marshall Zelinger regarding calls to change the name of Denver’s “Stapleton” neighborhood, which is named after the former Mayor.

Among those materials are newspaper clippings documenting Stapleton’s mayoral win and the support he received from the Klan, in addition to a photo of a page of the KKK’s register book that lists Stapleton as a member.

A Colorado Open Records Act (CORA) request for correspondence between members of the Stapleton family and high-level History Colorado employees during the time the museum developed its new KKK display and moved to its new building was unsuccessful, as that correspondence was apparently deleted.

History Colorado’s Chief Administration Officer Michelle Zale told the Colorado Times Recorder that emails of former employees are deleted upon termination of employment with the museum, and that the museum could not produce any pertinent documents as a result. Zale added that the accounts are deactivated by the Governor’s Office of Information Technology, and suggested submitting a request to that office. But that request was unsuccessful as well, and OIT’s Michael Shea said he had “no idea who would have custody of these records.”

History Colorado Collections Director Elisa Phelps, who provided the photos of the old KKK display, signaled changes to the museum’s exhibit development process over the years.

“There is room for improvement in creating archival documentation of exhibits but the development process itself has changed from being curatorially driven to involving multiple parties,” said Phelps.

“20-ish years ago exhibits were developed primarily by the curators which was great in terms of research and scholarship but not always the best approach for audience engagement and a broader perspective,” Phelps explained in an email. “As we planned for exhibits in the new building we followed a different model with an exhibit developer (that’s a newer role within the museum field–part of their role is to serve as an advocate for the audience and their needs) leading the development of the exhibit. In that model, the curator serves as a subject matter expert and the collection specialist while the overall interpretive approach is vested in the exhibit developer.”

In an interview with the Colorado Times Recorder, Denver historian Phil Goodstein, who authored In the Shadow of the Klan: When the KKK Ruled Denver, doubted the integrity of History Colorado as a public institution, saying that “it’s plenty of public money, but private money controls it.”

Asked if he saw any historical justification for leaving Mayor Stapleton off the display, Goodstein answered, “because you buy history the same way you buy everything else.”

Goodstein also described their exhibition development process as “political,” and doubted that the museum has clear “professional standards,” pointing to their controversial display on the Sand Creek Massacre, during which U.S. soldiers murdered more than 150 Cheyenne and Arapahoe villagers, many of whom were women and children, in an unprovoked attack.

The museum didn’t consult with tribal leaders during the exhibition development process, despite being legally required to, and when the North Cheyenne Tribe was eventually looped in, they had some concerns about the museum’s portrayal of the massacre. Their suggestions were never adopted, and History Colorado was never able to get it right, apparently, because that exhibit has since been closed.

History Colorado also faced backlash for their exhibit of Camp Amache, a Japanese internment camp, which critics said was made to look much cushier than the dismal conditions to which the Japanese-Americans were actually subjected. Following complaints, the museum put up a sign next to the exhibit explaining that the barracks were not to scale.

Asked about his gut reaction as to whether Barlock’s accusation could be valid, Goodstein responded, “That’s the way history ends up being written by the victors.”